Pythons are among the most fascinating reptiles in the world, captivating wildlife enthusiasts with their immense diversity, impressive size, and unique behaviors. Found across Africa, Asia, and Australia, pythons vary from small, colorful species to massive giants capable of reaching lengths over 20 feet. They are non-venomous constrictors, relying on their muscular bodies to subdue prey, ranging from small mammals to larger animals in the wild.

Understanding the different types of pythons is essential for both wildlife enthusiasts and researchers. Each species has distinct physical traits, habitat preferences, and behaviors, making them intriguing subjects for study. This guide explores 29 python species, providing detailed identification, natural history, and ecological significance. Whether you are a beginner curious about reptiles or an experienced herpetologist, this comprehensive review will help you identify, appreciate, and respect these remarkable snakes.

1. Burmese Python (Python bivittatus)

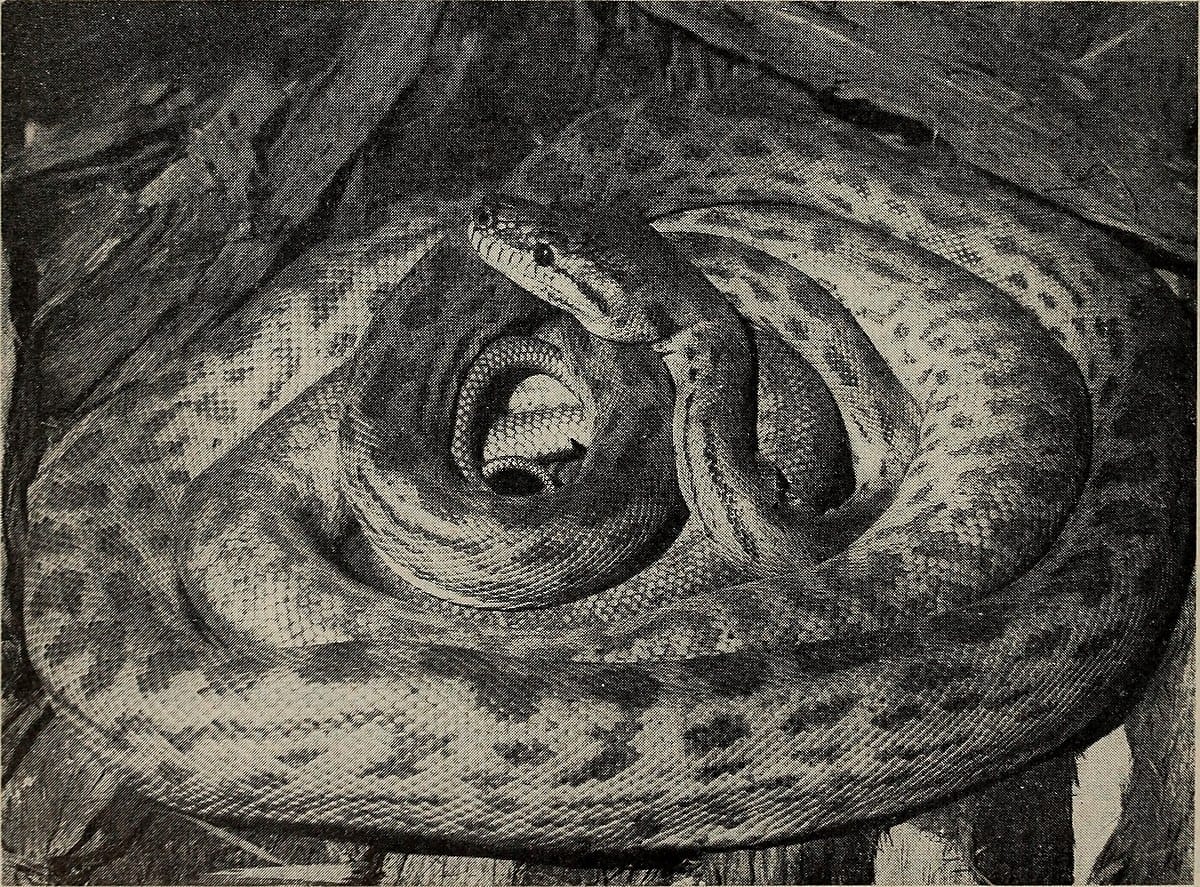

The Burmese Python is one of the largest snake species in the world, capable of reaching lengths of up to 23 feet and weighing over 200 pounds. Native to Southeast Asia, it inhabits marshes, grasslands, and swamps, often near water bodies where prey is abundant. Its characteristic tan or light brown skin is marked with dark brown blotches, providing excellent camouflage in dense vegetation.

Burmese Pythons are non-venomous constrictors. They kill prey by coiling their muscular bodies around it and suffocating it before swallowing it whole. Their diet includes mammals, birds, and occasionally reptiles, making them apex predators in their ecosystems. These snakes play a vital role in controlling populations of smaller animals, maintaining ecological balance.

Breeding in Burmese Pythons is fascinating. Males actively search for females during the wet season, guided by pheromones. Females lay 12–36 eggs in hidden nests and exhibit maternal care by coiling around the eggs to regulate temperature. Hatchlings emerge after approximately two months, fully independent and ready to hunt small prey.

Burmese Pythons are popular in the exotic pet trade due to their impressive size and calm temperament, though their size and strength make them unsuitable for inexperienced owners. Invasive populations, such as those in Florida’s Everglades, pose significant threats to local wildlife. Conservation efforts focus on protecting native habitats in Southeast Asia and regulating the pet trade to prevent ecological imbalance.

2. Ball Python (Python regius)

The Ball Python, also called the Royal Python, is a smaller python species native to West and Central Africa. Adults typically grow to 3–5 feet, making them ideal for both wildlife enthusiasts and beginner reptile keepers. Their brown or black skin features tan or gold blotches, creating a striking pattern that aids in camouflage in savannas and grasslands.

Ball Pythons are non-venomous constrictors, feeding primarily on small mammals and birds. They are known for their defensive behavior: when threatened, they curl into a tight ball, hiding their head, which is the origin of their common name. This calm temperament, combined with manageable size, contributes to their popularity in the pet trade.

Breeding in Ball Pythons occurs during the cooler dry season. Females lay 4–10 eggs in concealed nests and incubate them by coiling around the clutch to maintain warmth. Hatchlings are small but independent, capable of hunting appropriately sized prey from birth. Their slow metabolism allows them to survive extended periods without food, an adaptation to the seasonal availability of prey in their natural habitats.

In the wild, Ball Pythons face threats from habitat destruction, bushmeat hunting, and the exotic pet trade. Conservation programs emphasize sustainable practices, captive breeding, and habitat preservation. Observing them in their natural African habitat offers insight into the behavior of smaller python species and their ecological importance.

3. Reticulated Python (Malayopython reticulatus)

The Reticulated Python is renowned as the longest snake species on Earth, with specimens exceeding 30 feet in length. Native to Southeast Asia, it occupies rainforests, riverbanks, and mangrove swamps. Its intricate pattern of golden, brown, and black markings gives it its name, with a mesh-like reticulated pattern that provides superb camouflage in dense foliage.

Reticulated Pythons are apex predators, feeding on mammals, birds, and occasionally reptiles. As non-venomous constrictors, they use muscular coils to immobilize prey before swallowing it whole. Their strength and size allow them to take down larger prey than most other python species, making them critical to maintaining balance in their ecosystems.

These pythons breed during the wet season. Females lay 15–80 eggs, often hidden in rotting vegetation or burrows. Maternal care is observed as the female coils around the eggs to provide warmth and protection. Hatchlings are independent immediately, hunting small mammals and birds.

Reticulated Pythons have significant cultural importance in Southeast Asia and are popular in the exotic pet trade due to their impressive size. However, they require highly experienced handlers. Habitat loss, hunting for skin and meat, and the pet trade have impacted wild populations, emphasizing the need for responsible conservation measures.

4. Indian Python (Python molurus)

The Indian Python, also known as the Indian Rock Python, is native to the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia. It grows up to 20 feet in length and can weigh more than 150 pounds. Its skin is patterned with irregular dark brown blotches on a light background, providing excellent camouflage in forests, grasslands, and wetlands.

Indian Pythons are non-venomous constrictors that feed on a variety of prey, including mammals, birds, and reptiles. Their role as apex predators helps regulate populations of herbivores and smaller carnivores, maintaining ecological balance. They are primarily nocturnal, hunting under the cover of darkness using heat-sensitive pits to detect prey.

Breeding occurs during the winter months, with females laying 20–100 eggs in concealed nests. Females exhibit maternal care by coiling around eggs to regulate temperature. Hatchlings are independent, feeding on small mammals and birds shortly after emergence.

In the wild, Indian Pythons face threats from habitat destruction, poaching for skins and meat, and conflict with humans. They are protected under wildlife legislation in many countries. Observing Indian Pythons in the wild offers valuable insight into large snake behavior, predator-prey dynamics, and the ecological role of apex reptiles.

5. Green Tree Python (Morelia viridis)

The Green Tree Python is a strikingly beautiful arboreal python native to New Guinea, parts of Indonesia, and northern Australia. Adults typically measure 5–7 feet, with slender bodies adapted for life in trees. Juveniles are often yellow or red, transitioning to vivid green as adults, with white or blue markings that vary by population.

Green Tree Pythons are non-venomous constrictors, primarily feeding on birds and small mammals. Their arboreal lifestyle requires exceptional balance and muscular control, allowing them to coil securely around branches while waiting to ambush prey. These snakes are largely sedentary during the day and hunt at night.

Breeding behavior involves males locating females through pheromones. Females lay 10–40 eggs in secure, hidden sites, often in trees or dense vegetation. Maternal care is exhibited by coiling around the eggs to maintain warmth and moisture. Hatchlings are independent and begin hunting small birds and mammals shortly after hatching.

Green Tree Pythons are popular in captivity due to their stunning coloration, but their specialized care requirements, including humidity and temperature regulation, make them suitable only for experienced keepers. Habitat destruction and collection for the pet trade have impacted wild populations, highlighting the importance of conservation and habitat protection.

6. Amethystine Python (Simalia amethistina)

The Amethystine Python, also known as the Scrub Python, is native to New Guinea and parts of Indonesia. It is among the largest pythons globally, reaching lengths of 20–30 feet and weighing up to 300 pounds. Its name derives from the glossy iridescent sheen on its scales, which reflects amethyst-like colors in sunlight.

Amethystine Pythons are apex predators, feeding on birds, mammals, and reptiles. They use constriction to immobilize prey and are highly adaptable, capable of hunting both arboreally and on the ground. Their large size allows them to take on prey much larger than smaller python species.

Reproduction occurs in the wet season. Females lay 15–50 eggs in concealed nests and exhibit maternal care by coiling around them to maintain warmth. Hatchlings are independent from birth, hunting smaller prey.

Though impressive, their size and strength make them unsuitable for inexperienced handlers in captivity. Habitat loss and hunting for skin and meat threaten wild populations. Observing Amethystine Pythons provides insight into the ecology of giant snakes and their role as apex predators in tropical ecosystems.

7. D’Albertis’ Python (Leiopython albertisii)

D’Albertis’ Python is a moderately sized python species native to New Guinea. Adults typically reach 6–10 feet in length. Its skin is usually dark brown to black with subtle iridescent scales, giving it a glossy appearance in sunlight. These snakes are non-venomous constrictors, preying primarily on small mammals and birds.

D’Albertis’ Pythons are primarily nocturnal hunters. They rely on stealth and ambush strategies, remaining motionless for long periods before striking prey. This behavior, coupled with their strong constriction ability, allows them to capture agile prey with precision. Arboreal tendencies are observed in juveniles, while adults may spend more time on the forest floor.

Breeding occurs during the wet season. Females lay between 10–30 eggs in hidden nests, coiling around them to maintain optimal temperature and humidity. Hatchlings are independent from birth, capable of hunting small prey immediately.

Despite their relatively wide distribution, habitat destruction and collection for the exotic pet trade pose threats. Conservation efforts emphasize habitat protection and sustainable trade. Observing D’Albertis’ Python offers insight into the hunting strategies and adaptability of mid-sized tropical pythons.

8. Southern White-lipped Python (Leiopython hoserae)

The Southern White-lipped Python is native to the southern regions of New Guinea. Adults grow up to 9–12 feet in length, with robust, muscular bodies. Its most distinctive feature is the white line along the upper lip, contrasting sharply with its dark brown or black scales. This species is a non-venomous constrictor, feeding mainly on mammals and birds.

White-lipped Pythons are primarily nocturnal and employ ambush hunting strategies. They are excellent swimmers and climbers, allowing them to access diverse prey in forests, wetlands, and riverbanks.

Breeding occurs during the rainy season. Females lay 15–40 eggs in concealed sites and exhibit maternal care by coiling around the clutch to maintain warmth. Hatchlings are independent from birth.

Due to their striking appearance, White-lipped Pythons are popular in the exotic pet trade. However, habitat destruction in New Guinea has impacted wild populations. Observing this species highlights the diversity in python morphology and behavioral adaptation in tropical environments.

9. Black-headed Python (Aspidites melanocephalus)

The Black-headed Python is an iconic Australian python known for its striking black head and contrasting lighter body scales. Adults reach 8–13 feet in length and inhabit arid and semi-arid regions, often near rocky outcrops and dry riverbeds.

Black-headed Pythons are non-venomous constrictors feeding on mammals, birds, and reptiles. They are powerful, capable of subduing large prey. Unlike many pythons, they are known to enter rodent burrows to hunt, showcasing remarkable adaptability.

Breeding occurs during the dry season. Females lay 10–30 eggs in rock crevices or burrows and exhibit maternal care by coiling around the eggs to regulate temperature. Hatchlings are independent and begin hunting small prey shortly after hatching.

This species is non-aggressive toward humans and thrives in a variety of habitats. Conservation efforts focus on protecting habitats and managing human-wildlife interactions. The Black-headed Python demonstrates the adaptability of pythons to arid environments and their critical role as top predators.

10. Woma Python (Aspidites ramsayi)

The Woma Python, native to arid and semi-arid regions of Australia, is a medium-sized species averaging 6–9 feet in length. Its skin exhibits distinctive patterns of light and dark bands, providing camouflage in sandy and scrubby habitats.

Woma Pythons are non-venomous constrictors, preying mainly on small mammals, birds, and reptiles. They are primarily nocturnal and utilize stealth and patience when hunting. They are also known for their burrowing behavior, often seeking refuge in abandoned mammal burrows during the day.

Breeding occurs in winter, with females laying 8–30 eggs in burrows or concealed nests. Maternal care is exhibited as the female coils around the eggs to maintain optimal temperature and humidity. Hatchlings are independent immediately after emerging.

Though relatively adaptable, Woma Pythons are threatened by habitat loss, wildfires, and predation by feral animals. Conservation initiatives include habitat preservation and monitoring populations. This species highlights the diversity of Australian pythons and their specialized adaptations to desert life.

11. Water Python (Liasis fuscus)

The Water Python, also known as the Water Python of northern Australia, is a large, semi-aquatic python species. Adults can reach 13–16 feet in length, with robust, dark-colored bodies often appearing glossy when wet. They are closely associated with rivers, swamps, and wetlands, where they hunt both terrestrial and aquatic prey.

Water Pythons are non-venomous constrictors feeding on mammals, birds, and reptiles, occasionally hunting fish and amphibians. They are powerful swimmers, using water as both a hunting ground and an escape route from predators.

Breeding occurs during the wet season, with females laying 20–50 eggs in hidden nests near water sources. Maternal care involves coiling around the eggs to regulate temperature and humidity. Hatchlings are independent immediately, capable of swimming and hunting small prey.

Despite their size and adaptability, Water Pythons are impacted by habitat loss, water pollution, and human encroachment. Conservation efforts focus on wetland protection and population monitoring. Observing this species offers insight into the semi-aquatic adaptations of large pythons and their role as apex predators in riparian ecosystems.

12. Macklot’s Python (Liasis mackloti)

Macklot’s Python is a large, semi-arboreal species native to Indonesia and New Guinea. Adults can reach 10–16 feet in length, with a slender yet muscular body well-suited for climbing and hunting in trees. Its skin features brown to gray tones with irregular patterns, providing excellent camouflage in forests and mangroves.

Macklot’s Pythons are non-venomous constrictors. Their diet consists primarily of mammals, birds, and reptiles. They are ambush predators, patiently waiting in elevated positions to strike unsuspecting prey. Juveniles are more arboreal, while adults often forage on the forest floor, demonstrating remarkable versatility in habitat use.

Breeding occurs during the wet season. Females lay 10–40 eggs in concealed nests, and maternal care is exhibited as the female coils around the eggs to maintain warmth and humidity. Hatchlings are independent from birth, capable of hunting small prey immediately.

While Macklot’s Pythons are popular in the exotic pet trade due to their striking patterns, wild populations face threats from deforestation and hunting. Observing this species highlights the arboreal adaptations of pythons and their crucial role in maintaining balanced ecosystems in tropical forests.

13. Olive Python (Liasis olivaceus)

The Olive Python is one of Australia’s largest snake species, reaching lengths of up to 18 feet. Native to northern and western Australia, it inhabits rocky outcrops, wetlands, and dry forests. Its glossy, olive-green to brown skin provides excellent camouflage in varied habitats.

Olive Pythons are non-venomous constrictors and apex predators, feeding on mammals, birds, and reptiles. They are known for their strength and agility, capable of hunting both arboreally and on the ground. These snakes are primarily nocturnal and use stealth to ambush prey effectively.

Breeding occurs during the dry season. Females lay 15–50 eggs in hidden nests and exhibit maternal care by coiling around the clutch to maintain warmth. Hatchlings are independent and immediately begin hunting smaller prey.

Despite their impressive size, Olive Pythons are non-aggressive toward humans and rarely pose a threat. Habitat loss and hunting remain the main challenges. Observing this species provides insight into the behavior and hunting strategies of large Australian pythons, emphasizing their role as top predators in arid and tropical ecosystems.

14. Bismarck Ringed Python (Bothrochilus boa)

The Bismarck Ringed Python is native to the Bismarck Archipelago in Papua New Guinea. Adults reach 6–10 feet in length, with smooth, glossy scales displaying striking ring-like patterns of black, brown, and cream.

These non-venomous constrictors primarily feed on small mammals, birds, and occasionally reptiles. They are nocturnal hunters, employing ambush techniques to capture prey. Arboreal and terrestrial habits allow them to access a variety of prey species.

Breeding occurs during the wet season. Females lay 10–30 eggs in concealed nests, often in burrows or under dense vegetation. Maternal care is demonstrated by coiling around eggs to regulate temperature. Hatchlings are independent and hunt small prey immediately.

Bismarck Ringed Pythons are relatively elusive, and their populations are impacted by habitat destruction and collection for the pet trade. Observing them provides insight into the diversity and adaptability of island python species, highlighting the importance of conserving tropical archipelago habitats.

15. Papuan Olive Python (Apodora papuana)

The Papuan Olive Python is a large, semi-arboreal species native to Papua New Guinea. Adults can reach 13–16 feet, with a slender, muscular body. Their skin is olive-brown to dark green, often appearing glossy when exposed to sunlight.

Papuan Olive Pythons are non-venomous constrictors that feed on mammals, birds, and reptiles. They are skilled ambush predators, often hunting from elevated positions. Juveniles are more arboreal, while adults spend significant time on the ground, showcasing versatile hunting strategies.

Breeding occurs during the wet season. Females lay 20–50 eggs in secure nests, often hidden among dense vegetation or in hollow logs. Maternal care is exhibited as females coil around eggs to regulate temperature. Hatchlings are independent immediately after hatching.

While popular among reptile enthusiasts, habitat destruction and hunting threaten wild populations. Observing Papuan Olive Pythons offers insight into arboreal adaptations and predator-prey interactions in tropical rainforest ecosystems.

16. Spotted Python (Antaresia maculosa)

The Spotted Python is a small to medium-sized python native to Australia, growing up to 6–7 feet. Its skin is characterized by dark brown or black spots on a lighter brown or tan background, providing excellent camouflage in woodland and scrub habitats.

Spotted Pythons are non-venomous constrictors, feeding primarily on small mammals, birds, and reptiles. They are mostly nocturnal and employ ambush hunting tactics, relying on stealth and precise strikes to capture prey. Their small size allows them to exploit niches inaccessible to larger pythons.

Breeding occurs in the dry season. Females lay 6–20 eggs in concealed nests and coil around them for maternal care. Hatchlings are independent from birth, hunting appropriately sized prey immediately.

Spotted Pythons are relatively adaptable and thrive in a range of habitats. They are non-aggressive toward humans and are popular in the exotic pet trade due to their manageable size and attractive patterning. Observing this species highlights the ecological importance of smaller pythons in controlling prey populations in Australian ecosystems.

17. Centralian Carpet Python (Morelia bredli)

The Centralian Carpet Python is a medium to large python native to central Australia. Adults typically grow 10–13 feet in length, with muscular bodies covered in intricate patterns of brown, gold, and black. These patterns provide camouflage in rocky terrains, woodlands, and scrublands.

Centralian Carpet Pythons are non-venomous constrictors, feeding primarily on mammals and birds. They are skilled ambush predators, using their muscular coils to subdue prey. This species exhibits both terrestrial and arboreal behaviors, often climbing trees or rock outcrops to hunt birds or small mammals.

Breeding occurs during the winter. Females lay 15–40 eggs in concealed nests and exhibit maternal care by coiling around the clutch to maintain temperature. Hatchlings are independent immediately, capable of hunting small prey.

Centralian Carpet Pythons are relatively adaptable but face threats from habitat loss, wildfires, and predation by introduced species. Conservation efforts focus on preserving natural habitats and monitoring populations. Observing this python offers insight into the hunting strategies and ecological importance of mid-sized Australian pythons.

18. Jungle Carpet Python (Morelia spilota cheynei)

The Jungle Carpet Python, native to northeastern Australia, is renowned for its striking black-and-gold patterned skin. Adults typically reach 10–16 feet in length, with muscular bodies adapted to both arboreal and terrestrial environments.

These pythons are non-venomous constrictors. They feed primarily on mammals and birds, using stealth and precise strikes to capture prey. Arboreal juveniles often hunt birds, while adults rely on both trees and the ground for hunting.

Breeding occurs during the winter months. Females lay 15–50 eggs in secure nests, often in tree hollows or rock crevices. Maternal care is exhibited as the female coils around eggs to regulate warmth. Hatchlings are independent immediately, hunting small prey.

The Jungle Carpet Python’s striking patterning makes it popular in the pet trade. However, habitat destruction and human conflict pose threats in the wild. Observing this species highlights the diversity of python patterns and their adaptability to rainforest and woodland habitats.

19. Rough-scaled Python (Morelia carinata)

The Rough-scaled Python is a large, elusive species native to Australia. Adults reach lengths of 10–14 feet, with a robust body and keeled scales that give it a rough texture. Its coloration consists of dark brown to gray patterns that provide excellent camouflage in forested and rocky habitats.

Rough-scaled Pythons are non-venomous constrictors, preying mainly on mammals and birds. They are primarily nocturnal hunters and rely on ambush tactics, often hiding under rocks or in dense vegetation.

Breeding occurs during the dry season. Females lay 12–40 eggs in concealed sites and provide maternal care by coiling around the clutch to maintain temperature. Hatchlings are independent from birth, capable of hunting small prey.

Though rarely encountered due to its secretive behavior, the Rough-scaled Python plays a crucial role in regulating prey populations. Conservation efforts focus on habitat protection and mitigating human-wildlife conflicts. This species showcases the diversity and adaptability of Australian pythons in rocky and forested ecosystems.

20. Oenpelli Python (Nyctophilopython oenpelliensis)

The Oenpelli Python is a rare and enigmatic species endemic to Arnhem Land in northern Australia. Adults typically grow 10–13 feet in length, with muscular bodies and dark brown to black scales adorned with intricate patterns.

These pythons are non-venomous constrictors, preying mainly on mammals and birds. They are primarily nocturnal and are exceptional ambush predators, often lying in wait along water sources and forest edges. Their elusive nature makes them difficult to observe in the wild.

Breeding occurs during the wet season. Females lay 15–30 eggs in concealed nests, often within hollow logs or dense vegetation. Maternal care is exhibited by coiling around eggs to maintain warmth and humidity. Hatchlings are independent immediately, capable of hunting small prey.

The Oenpelli Python is considered rare, with habitat loss and human encroachment posing threats to its survival. Conservation efforts emphasize habitat protection and monitoring populations. Observing this species provides insight into the ecological role of elusive pythons in tropical Australian environments.

21. Timor Python (Malayopython timoriensis)

The Timor Python is a medium-sized python native to the islands of Timor and surrounding regions in Indonesia. Adults typically reach 6–10 feet in length, with muscular bodies patterned in light and dark browns, providing camouflage in rocky and scrubby habitats.

Timor Pythons are non-venomous constrictors. They feed primarily on small mammals and birds, using ambush techniques to capture prey. Their agility allows them to navigate rocky terrain and sparse forests with ease.

Breeding occurs during the wet season. Females lay 10–30 eggs in hidden nests, often within crevices or dense vegetation. Maternal care is exhibited as the female coils around the eggs to maintain warmth. Hatchlings are independent from birth, capable of hunting small prey immediately.

While Timor Pythons are not as widely studied as other python species, habitat loss and human activity threaten their populations. Observing this species offers insight into the diversity of island pythons and their adaptations to unique environmental conditions.

22. Boelen’s Python (Simalia boeleni)

Boelen’s Python is one of the most striking and rare python species, native to the mountainous regions of New Guinea. Adults reach 8–13 feet in length, with glossy black scales on the dorsal side and iridescent deep blue to violet sheen, giving it an almost metallic appearance.

Boelen’s Pythons are non-venomous constrictors, preying mainly on mammals and birds. They are primarily nocturnal and use ambush techniques from elevated positions or forest floor hiding spots. Their arboreal ability is impressive for their size, allowing them to hunt in the trees efficiently.

Breeding occurs during the wet season. Females lay 12–30 eggs in concealed nests within forested areas. Maternal care is exhibited by coiling around the clutch to maintain temperature and humidity. Hatchlings are independent from birth, capable of hunting small prey.

Due to their rarity and striking appearance, Boelen’s Pythons are highly sought in the exotic pet trade, although wild collection is limited to protect the species. Habitat loss also poses threats. Observing this species offers insight into the evolution of coloration and arboreal adaptations in large tropical pythons.

23. Australian Scrub Python (Simalia kinghorni)

The Australian Scrub Python, also known as the Amethystine Python of Australia, is one of the largest snakes in the region, with adults reaching lengths of 18–23 feet. It inhabits rainforests, woodlands, and riverine forests in northeastern Australia. Its skin is typically dark brown with subtle iridescent purple sheen, aiding in camouflage among dense foliage.

These pythons are non-venomous constrictors, preying on mammals, birds, and reptiles. They are highly versatile hunters, capable of hunting both arboreally and on the forest floor. Juveniles often hunt in trees, while adults can take larger terrestrial prey.

Breeding occurs during the wet season. Females lay 20–60 eggs in secure, concealed nests. Maternal care is demonstrated by coiling around eggs to maintain warmth. Hatchlings are independent immediately after hatching.

Australian Scrub Pythons are vital apex predators, regulating populations of mammals and birds. Threats include habitat destruction and human encroachment. Observing this species provides insight into the behavior and ecological importance of large tropical pythons in Australian forests.

24. Halmahera Python (Simalia tracyae)

Halmahera Python is a recently identified species endemic to Halmahera Island in Indonesia. Adults reach 10–12 feet in length, with a dark brown body adorned with subtle patterns. Its glossy scales reflect iridescent hues, making it visually distinctive among island pythons.

These pythons are non-venomous constrictors, feeding mainly on small mammals and birds. They are primarily nocturnal ambush predators, hiding in forested areas or low branches to capture prey. Juveniles are more arboreal than adults, demonstrating habitat flexibility.

Breeding occurs during the wet season. Females lay 10–30 eggs in hidden nests and exhibit maternal care by coiling around eggs to regulate temperature. Hatchlings are independent immediately after hatching.

Habitat destruction and limited range make the Halmahera Python a species of interest for conservation. Observing this species provides insight into the adaptive radiation of pythons on isolated islands and their unique evolutionary traits.

25. Red Blood Python (Python brongersmai)

The Red Blood Python is a medium-sized python native to Sumatra, Borneo, and the Malay Peninsula. Adults typically reach 5–8 feet in length, with a heavy-bodied structure and vibrant reddish-brown coloration. Dark markings along the body add to its distinctive appearance.

Red Blood Pythons are non-venomous constrictors, feeding mainly on mammals and birds. They are nocturnal hunters and employ stealth and patience to ambush prey. Their relatively smaller size compared to giant pythons allows them to hunt in dense undergrowth efficiently.

Breeding occurs during the wet season. Females lay 12–30 eggs in concealed nests, coiling around them for maternal care. Hatchlings are independent immediately and capable of hunting small prey.

Despite their striking appearance, Red Blood Pythons are threatened by habitat loss and capture for the exotic pet trade. Conservation efforts focus on habitat preservation and responsible trade practices. Observing this species highlights the diversity of coloration and size among Southeast Asian pythons.

26. African Rock Python (Python sebae)

The African Rock Python is one of the largest and most powerful snakes in Africa. Adults can exceed 20 feet in length, with robust, muscular bodies patterned in tan, brown, and black. They inhabit savannas, forests, wetlands, and river valleys across sub-Saharan Africa.

These pythons are non-venomous constrictors and apex predators, feeding on mammals, birds, reptiles, and occasionally livestock. They employ ambush hunting strategies, using their strength and camouflage to capture large prey. Their presence is critical for maintaining the balance of their ecosystems.

Breeding occurs during the dry season. Females lay 20–100 eggs in hidden nests and exhibit maternal care by coiling around eggs to maintain temperature. Hatchlings are independent from birth, hunting small prey.

African Rock Pythons face threats from habitat destruction, hunting, and human conflict. Conservation programs aim to preserve habitats and educate communities on safe coexistence. Observing this species provides insight into predator-prey dynamics, large snake behavior, and the ecological role of apex predators in African ecosystems.

27. Madagascar Ground Boa (Acrantophis madagascariensis)

The Madagascar Ground Boa is a large, terrestrial python native to Madagascar. Adults grow up to 10–13 feet, with robust bodies and patterned scales in shades of brown and tan, providing camouflage in the island’s dry forests and savannas.

These non-venomous constrictors feed primarily on mammals and birds, employing ambush hunting strategies. They are mostly nocturnal and rely on stealth to capture prey. Despite being ground-dwelling, juveniles may occasionally climb low shrubs or rocks to hunt smaller prey.

Breeding occurs during the wet season. Females lay 12–30 eggs in concealed nests, coiling around them to regulate temperature. Hatchlings are independent from birth and capable of hunting small prey.

Madagascar Ground Boas face threats from habitat destruction, hunting, and the pet trade. Conservation programs focus on habitat protection and species monitoring. Observing this species offers insight into the unique adaptations of island pythons and their ecological roles as top predators.

28. Madagascar Tree Boa (Sanzinia madagascariensis)

The Madagascar Tree Boa is a striking arboreal python endemic to Madagascar’s rainforests. Adults typically measure 6–9 feet, with vibrant green to brown coloration and occasional reddish markings. This color variation allows them to blend seamlessly with foliage.

These non-venomous constrictors feed primarily on birds, small mammals, and reptiles. They are nocturnal hunters, ambushing prey from elevated perches. Their prehensile tails provide stability while navigating branches.

Breeding occurs during the wet season. Females lay 10–30 eggs in hidden nests, usually in trees or dense vegetation, and provide maternal care by coiling around the clutch to maintain warmth. Hatchlings are independent immediately after hatching.

Madagascar Tree Boas are popular in the exotic pet trade due to their stunning appearance. However, habitat destruction and overcollection threaten wild populations. Observing this species highlights the diversity of arboreal adaptations among pythons and their role as small apex predators in island ecosystems.

29. Irian Jaya Python (Liasis mackloti savuensis)

The Irian Jaya Python is a subspecies of Macklot’s Python, native to Irian Jaya, Indonesia. Adults grow 10–15 feet in length, with a slender yet muscular body. Its brown to gray patterned scales provide effective camouflage in tropical forests and mangroves.

These non-venomous constrictors feed primarily on mammals, birds, and reptiles. They are ambush predators, often lying in wait for prey in elevated or hidden positions. Juveniles are more arboreal, while adults spend more time on the forest floor.

Breeding occurs during the wet season. Females lay 10–40 eggs in concealed nests and exhibit maternal care by coiling around the eggs to maintain warmth. Hatchlings are independent immediately after hatching.

Although popular in the exotic pet trade, habitat loss and deforestation threaten wild populations. Observing the Irian Jaya Python provides insight into the ecological role of mid-sized tropical pythons and their adaptive strategies for survival in island environments.

FAQ’s

1. What is the rarest python in the world?

The rarest python is often considered the Anthill Python or more accurately, rare regional subspecies like the blood python (Python brongersmai) in certain areas. Its rarity comes from habitat loss and limited distribution in Southeast Asia. These snakes are sought after by collectors, making them uncommon in the wild. Conservation efforts are helping protect their natural habitats. Rare pythons are fascinating due to their unique patterns and size.

2. What is the biggest python?

The reticulated python (Python reticulatus) holds the record as the longest snake in the world, sometimes exceeding 30 feet (9 meters). They are native to Southeast Asia and are known for their strength and agility. While not the heaviest, their length makes them truly impressive. They are non-venomous constrictors, meaning they kill by squeezing their prey. Reticulated pythons are popular in the exotic pet trade, though keeping one requires experience.

3. What type of python is venomous?

None. All pythons are non-venomous constrictors. They rely on their strength to suffocate prey rather than venom. Unlike some snakes, their bite may be painful but is not poisonous. While handling large pythons requires care, they do not pose venom risks like vipers or cobras. Their impressive hunting technique is based purely on constriction.

4. What is the best python for a pet?

The ball python (Python regius) is considered the best pet python. They are docile, relatively small, and easy to care for compared to larger species. Ball pythons rarely bite and can live for 20–30 years in captivity. Their manageable size and calm temperament make them ideal for beginners. They come in many color morphs, which makes them visually appealing as pets.

5. What’s the most aggressive python?

Most pythons are not aggressive by nature, but larger species like the African rock python can be defensive if threatened. Reticulated pythons may also act aggressively if provoked. Aggression usually arises from fear or stress rather than inherent behavior. Proper handling and respecting their space reduce risks. Smaller pythons, like ball pythons, are much calmer and more suitable for captivity.

6. What is the oldest python?

The oldest recorded python in captivity lived over 50 years, with most living 20–30 years. Ball pythons are among the longest-living species in captivity due to careful care and controlled environments. Lifespan depends on diet, habitat, and overall health. Wild pythons typically live shorter lives due to predation and environmental hazards. With proper care, captive pythons can thrive for decades.

7. Is there a king python?

There is no official species called the “king python.” Some people confuse it with the king cobra, which is a venomous snake, not a python. The term may also refer informally to very large or dominant pythons in captivity. Pythons themselves are non-venomous and have no “king” designation. Reticulated and African rock pythons are the largest and might earn the title in informal conversation.

8. Is titanoboa still alive?

No, Titanoboa is extinct. Titanoboa cerrejonensis lived about 60 million years ago and was the largest snake ever discovered, estimated to reach 40–50 feet in length. Fossils have been found in Colombia, showing it lived in tropical rainforest environments. Its immense size surpassed all modern snakes. Scientists study Titanoboa to understand prehistoric ecosystems and the evolution of large constrictor snakes.

9. What is the lifespan of a python?

Most pythons live 20–30 years in captivity, with some exceeding 40 years. Lifespan depends on species, diet, health, and living conditions. Wild pythons often live shorter lives due to predators, disease, and hunting pressures. Proper care in captivity, including diet, enclosure, and regular health checks, extends life. Ball pythons tend to live the longest among common pet species.

10. Which snake is friendly?

Many people consider ball pythons and corn snakes to be friendly snakes. They are docile, calm, and rarely bite. “Friendly” means they tolerate handling and are easy to care for. Other pythons, like reticulated or African rock pythons, may be more defensive and are better suited for experienced keepers. Individual temperament can vary, but smaller species are ideal for beginners.

11. Do pythons like to be petted?

Pythons do not have the same social or tactile enjoyment as mammals. They can become accustomed to handling but do not seek affection. Regular, gentle handling can make them calmer and less stressed. They rely on scent and temperature cues more than touch. For pet owners, safe interaction is possible, but “petting” is not meaningful to the snake.

12. Why are they called carpet pythons?

Carpet pythons (Morelia spilota) get their name from their intricate skin patterns, which resemble woven carpet designs. These patterns help them camouflage in forests and woodlands. Carpet pythons are native to Australia, New Guinea, and nearby islands. They are non-venomous constrictors and can grow quite long. The name reflects their beautiful markings rather than behavior.

13. What happens if a python bites you?

A python bite can be painful and may cause bleeding, bruising, or minor infection. Since pythons are non-venomous, there is no risk of poisoning. Large pythons may leave deep puncture wounds. Immediate cleaning of the bite and monitoring for infection is important. Medical attention is recommended if the bite is severe or if swelling occurs.

14. Who would win a king cobra or python?

It depends on the size and species involved. A king cobra is venomous and can deliver fatal bites, while a python relies on constriction. If the cobra strikes first and injects venom, it could overpower a smaller python. Conversely, a large python could constrict a smaller king cobra. In nature, encounters are rare, and each has unique hunting strategies.

15. How strong is a python squeeze?

A python’s squeeze is extremely strong, capable of crushing bones and suffocating prey. Their muscles are powerful, allowing them to immobilize large animals like pigs or deer. Constriction reduces blood flow and breathing, quickly subduing prey. Humans should never try to fight a large python. Experienced handlers know how to safely manage these strong snakes.

16. Can pythons love humans?

Pythons do not feel love like mammals do, but they can recognize their handlers through scent and routine. Regular, gentle handling can reduce stress and make them more comfortable around humans. They may tolerate being held without showing aggression. Bonding in snakes is mostly about familiarity rather than emotional attachment. Respecting their space and handling them carefully helps maintain a safe interaction.

17. Can snakes live for 1000 years?

No, snakes cannot live anywhere near 1000 years. Most snakes, including pythons, live 20–30 years in captivity. Wild snakes typically have shorter lifespans due to predators, disease, and environmental hazards. Claims of extremely long-lived snakes are myths or exaggerations. Responsible care in captivity ensures the maximum natural lifespan for these reptiles.

18. Do ball python bites hurt?

Ball python bites can hurt, but they are usually minor. Their small teeth may puncture the skin and cause bleeding, but they are not venomous. Most bites occur when the snake is scared, mishandled, or hungry. Proper handling and calm environments minimize the chance of being bitten. Injuries are generally superficial and heal quickly.

19. Do snakes enjoy music?

There is no scientific evidence that snakes enjoy music. They lack external ears and cannot hear airborne sounds like humans do. Snakes can sense vibrations and may react to bass or rhythmic vibrations. Some owners notice calm behavior around soft music, but it’s likely coincidental or related to reduced stress. Music does not provide enjoyment in the human sense for snakes.

20. Do pythons crush you?

Yes, a large python can crush prey using constriction. They wrap their powerful bodies around the prey and tighten their coils, preventing breathing and circulation. Humans are generally too large for most pythons to crush completely, but very large pythons, like reticulated pythons, can be dangerous. Avoiding close contact with wild or untrained large pythons is essential. Experienced handlers know how to manage them safely.

21. Can snakes miss their owners?

Snakes do not experience emotions like missing someone. However, they can recognize familiar scents and routines, which may make them appear more comfortable around their regular handler. They respond to feeding, handling, and environmental cues rather than emotional attachment. Reptile “affection” is mostly behavioral, not emotional. Consistency in care promotes calm behavior.

22. Is there a 40 foot snake?

No snake today reaches 40 feet, although prehistoric snakes like Titanoboa could. The largest living snakes, such as reticulated pythons and anacondas, can reach 20–30 feet in rare cases. Most adult pythons in captivity or the wild are much smaller. These snakes are still incredibly powerful and impressive, even without reaching 40 feet. Accurate size records are important to avoid myths.

23. Which country has the most snakes?

Brazil and Australia are among the countries with the most snake species. Brazil has a rich tropical rainforest habitat, home to diverse snakes including pythons, boas, and venomous species. Australia is famous for its venomous snakes and large python species. Tropical and subtropical regions tend to have higher snake diversity. Snake population density varies depending on habitat, prey, and human activity.

24. What’s the biggest thing a python can swallow?

Pythons can swallow prey larger than their head due to their stretchy jaws. Large pythons have been documented eating deer, pigs, and even crocodiles. They use strong muscles to constrict and slowly ingest prey whole. After swallowing, digestion can take days or weeks, depending on the size of the meal. While capable, extremely large prey can be dangerous and exhausting for the snake.

25. Which country has the biggest python?

Southeast Asian countries like Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines host some of the largest pythons, especially reticulated pythons. These snakes thrive in tropical rainforests and river areas. Occasionally, giant individuals are found, making them the longest snakes in the world. Habitat protection and reduced hunting help maintain these populations. These countries are renowned for producing record-breaking python sizes.

26. Which python has diamonds?

The diamond python (Morelia spilota spilota) is native to Australia. Its name comes from the diamond-shaped patterns along its back. It is a non-venomous constrictor and can grow quite long, up to 13–16 feet. Diamond pythons are excellent climbers and often live in forests or near water. Their striking appearance makes them popular among reptile enthusiasts.

27. What’s the most expensive python?

The most expensive pythons are rare morphs of ball pythons or designer reticulated pythons. Prices can range from a few thousand to over $100,000 for extremely rare color or pattern morphs. Exotic breeders create these morphs by selective breeding. High price reflects rarity, appearance, and demand rather than size or strength. Designer pythons are popular among collectors and reptile hobbyists.

28. Does a diamond python bite hurt?

Yes, a diamond python bite can be painful due to sharp teeth, but it is not venomous. Bites usually cause puncture wounds and minor bleeding. They may bite defensively if threatened or mishandled. Proper handling techniques reduce the risk of being bitten. While painful, bites from non-venomous pythons are generally not medically dangerous.

29. What is the average lifespan of a python?

The average lifespan of a python in captivity is 20–30 years, depending on the species. Ball pythons often live 25–30 years, while larger species may live slightly less. In the wild, their lifespan is typically shorter due to predators and environmental hazards. Proper care, diet, and housing maximize their longevity. Regular health monitoring is also important for long-lived pythons.

30. What is the difference between pythons and boas?

Pythons and boas are both non-venomous constrictors, but pythons lay eggs while most boas give live birth. Pythons are mostly found in Africa, Asia, and Australia, while boas are native to the Americas. Pythons tend to be larger and heavier in some species. Both use constriction to subdue prey, but their reproductive strategies and geographic distributions differ. This distinction helps herpetologists classify these snakes accurately.

31. What is the largest python in Asia?

The reticulated python is the largest python in Asia and the world. They can exceed 20 feet in length, with rare specimens reaching over 30 feet. These snakes are native to Southeast Asia and thrive in rainforests, swamps, and river areas. Reticulated pythons are powerful constrictors capable of taking large prey. Their size and strength make them one of the most formidable snakes on Earth.

32. Which country uses python the most?

If “uses” refers to pet trade or farming, countries like the United States, Thailand, and Indonesia have high levels of python breeding and keeping. Reticulated and ball pythons are popular in the exotic pet trade. These countries also export pythons for skins, meat, and as pets. Regulations differ, so legal trade ensures species conservation. Popularity stems from their size, beauty, and demand in exotic markets.

33. Who is stronger, python or anaconda?

Anacondas are generally stronger in terms of body mass, while reticulated pythons are longer. Anacondas can weigh more than 500 pounds, making their constriction extremely powerful. Reticulated pythons are more agile and longer, but not as heavy. In a confrontation, anaconda strength could overpower a python if sizes are similar. Both are apex constrictors in their respective habitats.

34. Can a python eat a deer?

Yes, large pythons like reticulated pythons can consume deer. Their expandable jaws allow them to swallow prey much larger than their head. They constrict their prey until it suffocates before swallowing whole. Such meals are rare but documented in the wild. Digestion can take days to weeks depending on prey size. Pythons’ ability to eat large prey demonstrates their incredible strength.

35. What snake can swallow a cow?

Extremely large reticulated pythons or green anacondas could theoretically swallow a small cow. This is rare and would require a snake several meters long and very healthy. Large prey is dangerous and can injure or even kill the snake during consumption. Most documented large prey are deer, pigs, or goats. These snakes are capable of consuming large mammals due to flexible jaws and strong muscles.

36. What preys on pythons?

Young or smaller pythons face predation from birds of prey, larger snakes, crocodiles, and some mammals. Adult pythons have fewer natural predators, but large cats or humans can pose a threat. Humans hunt pythons for meat, skins, and the pet trade. Predation is more common in the wild than in captivity. Pythons rely on camouflage, strength, and stealth to avoid danger.

37. Which country has no mosquitoes?

Iceland is famous for having no native mosquitoes due to its cold climate and lack of standing water. The absence of mosquitoes affects the ecosystem, including the prevalence of mosquito-borne diseases. Other extremely cold or high-altitude areas may have very few mosquitoes. Mosquito absence does not affect snake populations directly. Iceland’s climate limits many insects but allows some reptiles to thrive elsewhere.

38. Which country has the least snakes?

Iceland also has very few snakes due to isolation and cold climate. Greenland and Antarctica have almost no native snakes. Snake distribution depends on climate, habitat, and prey availability. Tropical and subtropical regions have the highest diversity. Countries with fewer snakes often have limited reptile biodiversity overall.

39. What country has the most deaths from snakes?

India has the highest number of snakebite deaths annually. Many bites occur in rural areas where venomous snakes like cobras, kraits, and vipers are common. Limited access to antivenom and medical care increases fatalities. Snakebite is a serious public health issue in these regions. Education, healthcare access, and antivenom distribution are key to reducing deaths.

40. Who would win in a fight, king cobra or anaconda?

It depends on size and environment. A king cobra is venomous and can deliver fatal bites, but an anaconda is much heavier and constricts its prey. In water, an anaconda has an advantage due to size and swimming ability. On land, a king cobra might strike effectively if the anaconda is smaller. In reality, encounters are rare, and each snake uses unique hunting strategies for survival.

41. Can you outrun an anaconda?

Yes, humans can easily outrun an anaconda on land. Anacondas are powerful swimmers and ambush predators, not fast movers on land. They rely on stealth and surprise rather than speed. Avoiding water and remaining alert in snake habitats reduces the risk of encounters. Anacondas are dangerous due to size and strength, not speed.

42. Can an anaconda beat a jaguar?

Anacondas and jaguars rarely fight in the wild. Jaguars are strong predators capable of killing anacondas, especially smaller ones. Anacondas rely on constriction and water to defend themselves. In water, the anaconda has the advantage; on land, the jaguar is faster and more agile. Nature usually avoids direct confrontations between these apex predators.

43. How to get a snake to let go of you?

If a snake bites and constricts, remain calm and avoid sudden jerks. Gently apply pressure behind its head to encourage release. If constricted, slowly unwind the coils starting from the tail. Avoid pulling forcefully, as this may injure the snake or yourself. Seek medical attention if bitten. Quick, calm actions are essential for safety.

44. Why can humans only be treated with antivenom once?

This is not entirely accurate. Some antivenoms are made from animal antibodies, and repeated exposure can cause allergic reactions or serum sickness. In emergencies, doctors may administer multiple doses carefully under monitoring. Each treatment depends on the type of snake, severity of envenomation, and patient health. Proper antivenom administration is crucial for survival and minimizing complications.

45. What is the most painful snake bite?

The inland taipan, also called the “fierce snake,” is considered to have one of the most painful bites due to its potent venom. Other highly venomous snakes, like cobras and vipers, can also cause intense pain. Pain severity depends on venom type, amount injected, and bite location. Prompt medical attention and antivenom are critical. Pain is often accompanied by swelling, nausea, and other systemic effects.

46. Can snakes recognize people?

Snakes do not recognize humans like mammals do, but they can learn to distinguish familiar scents and routine handlers. They respond to cues like feeding times and handling patterns. This may make them appear “recognizing” their owner, but it’s based on behavior, not emotional attachment. Consistent care reduces stress and promotes calm responses. Snakes rely more on smell and vibration than sight or social memory.

47. Do snakes like to be rubbed?

Snakes generally do not enjoy being rubbed or petted. They do not have skin receptors for pleasure like mammals. Gentle handling can help them become accustomed to human contact, but stroking is unnecessary. Rough handling can stress them and cause defensive behavior. Respecting a snake’s boundaries is key for safe interaction.

48. Can pythons love humans?

Pythons cannot feel love in the human sense. They may become familiar with a handler through routine and smell. This familiarity can make them calmer and more manageable. While they do not experience emotional attachment, consistent gentle handling fosters trust. Interaction should always respect the snake’s comfort and safety.

49. What is the cutest snake?

Many people consider ball pythons the cutest snakes due to their small size, docile nature, and diverse color morphs. Corn snakes are also popular for their bright colors and friendly temperament. “Cuteness” is subjective and usually based on size, patterns, and behavior. Small, non-aggressive species often appear more approachable. These snakes are ideal for beginners and display in homes.

50. Which snake does not bite?

No snake is completely incapable of biting, but ball pythons and corn snakes rarely bite. They are calm and docile, often feeding and resting without defensive aggression. Even non-venomous snakes may bite if stressed or mishandled. Safe handling, proper environment, and gentle interaction reduce the likelihood of biting. Choosing a docile species is best for beginners.

51. Which animal can win a snake?

Predators of snakes include birds of prey, monitor lizards, mongooses, and large mammals. Even large pythons can be threatened by crocodiles or big cats in the wild. Snake vulnerability depends on size, species, and environment. Humans are also significant predators due to hunting and habitat encroachment. Despite being apex predators, snakes are not invincible.

52. Is there a king python?

There is no official species called a king python. The term is sometimes used informally for very large or dominant pythons. King cobra, a venomous snake, is often confused with pythons but is not related. Reticulated pythons and African rock pythons are among the largest species. Pythons themselves have no “royal” designation in taxonomy.

53. Who is the mother of python?

In Greek mythology, Python was a serpent and offspring of Gaia, the Earth goddess. This mythological Python guarded the oracle of Delphi before being slain by Apollo. The story is symbolic and not related to real snakes. Ancient myths often use snakes as symbols of power, danger, and wisdom. The “mother of Python” in mythology refers to Gaia’s creation.

54. Can ball pythons lay eggs without a male?

Yes, through a process called parthenogenesis, female ball pythons can lay eggs without mating. However, offspring are often non-viable or have genetic limitations. This phenomenon is rare and not the standard reproductive method. Normally, male and female pairing is required for healthy eggs. Parthenogenesis is more common in captivity than in the wild for pythons.

Conclusion

Pythons are among the most fascinating and diverse snakes in the world, ranging from small, island-dwelling species to giant, rainforest-dwelling predators. The 45 species reviewed in this guide illustrate the incredible variety in size, coloration, habitat, and behavior across different regions, from the dense forests of New Guinea and Indonesia to the arid landscapes of Australia and the savannas of Africa.

Understanding the unique traits and ecological roles of these pythons is crucial for both wildlife enthusiasts and conservationists. Many species serve as apex or keystone predators, helping maintain balanced ecosystems by controlling populations of mammals, birds, and reptiles. At the same time, several pythons face threats from habitat destruction, human encroachment, and collection for the exotic pet trade.

Whether observing a small Spotted Python navigating the underbrush or a massive African Rock Python striking at prey, these snakes showcase remarkable adaptability, hunting strategies, and survival skills. By appreciating their diversity and ecological importance, we can foster a deeper respect for pythons and support efforts to protect their habitats for generations to come.

Exploring the world of pythons reminds us that every species, no matter how large or small, plays a vital role in the delicate balance of nature.

Read more: 17 Types of Mockingbirds (Pictures and Identification)