Mosquitos are more than just pesky insects that make our summer nights uncomfortable. Understanding the different types of mosquitos is important for both health and curiosity. With over 3,500 species worldwide, some mosquitos are vectors for serious diseases like malaria, dengue, and Zika virus, while others are harmless. In this article, we explore 40 distinct mosquito species, highlighting their appearance, behavior, habitats, and identification tips. This guide is designed to help beginners recognize common and medically important mosquitos and understand their role in nature. By the end, you’ll know how to spot these insects and appreciate their ecological role while staying safe.

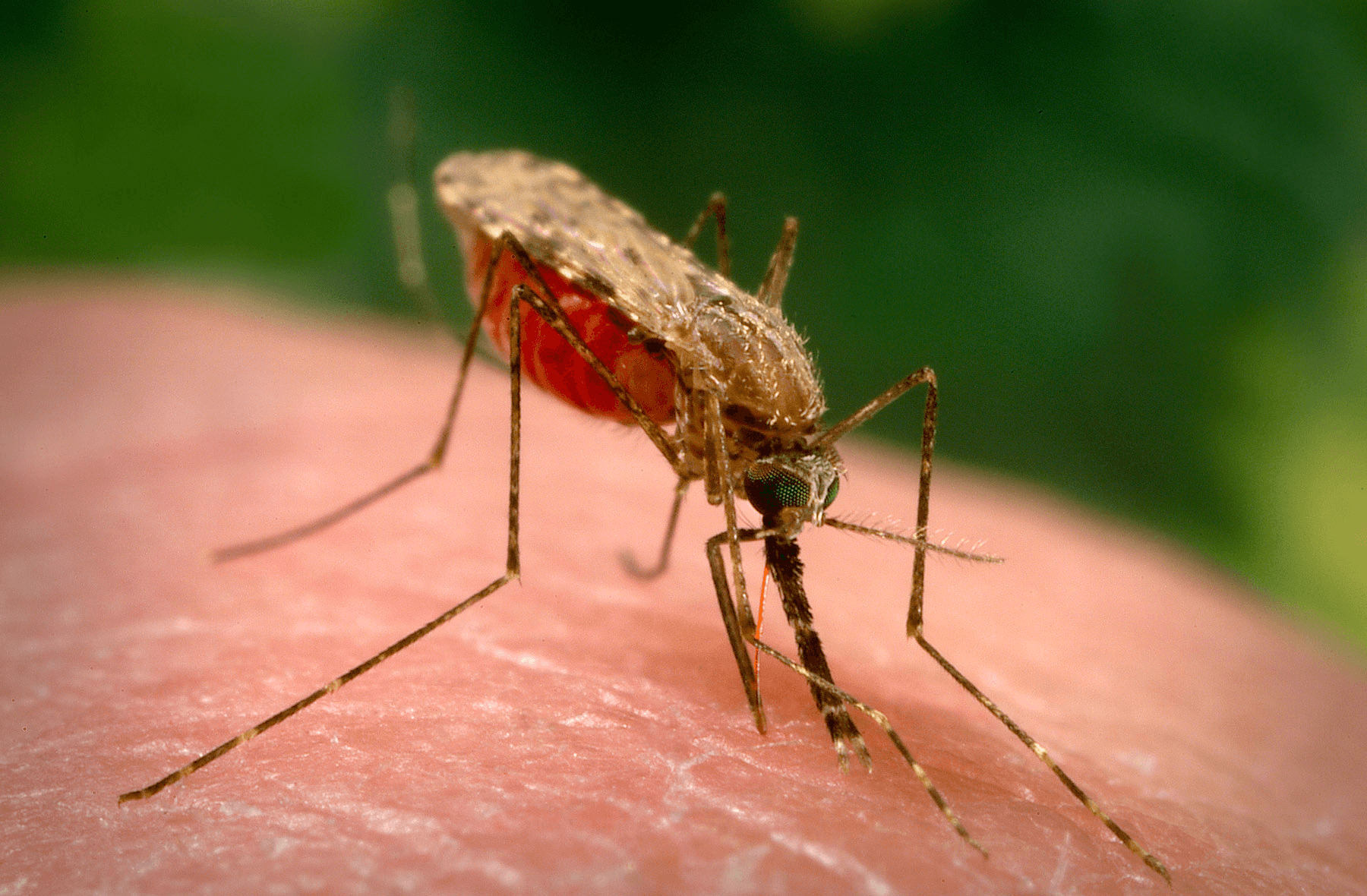

1. Anopheles gambiae

Anopheles gambiae is one of the most notorious mosquitos globally, primarily because it is a major vector of malaria. Native to Sub-Saharan Africa, this mosquito thrives in tropical climates where standing water is abundant. Identification is possible thanks to its slender body, spotted wings, and resting posture, which is angled relative to the surface. Unlike other mosquitoes, it tends to feed at night, often preferring humans over animals, which contributes to malaria transmission. Females are the blood-feeding sex, and males feed on nectar. Anopheles gambiae’s larvae develop in small, sunlit pools, rice paddies, or temporary puddles. Interestingly, this species exhibits behavioral adaptations like indoor feeding and resting, which allow them to survive close to human settlements. Understanding its life cycle and habits is crucial for disease control strategies and public health measures. Observing these mosquitoes in nature requires caution and protective measures, but it also offers insights into vector ecology and the delicate balance of ecosystems.

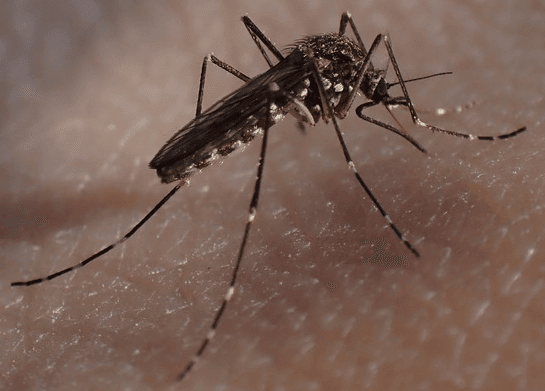

2. Aedes albopictus (Asian Tiger Mosquito)

The Asian Tiger Mosquito, or Aedes albopictus, is easily recognized by its striking black-and-white striped legs and body. Originally native to Southeast Asia, it has spread globally through trade and travel, especially in used tires and ornamental plants. This mosquito is aggressive and bites during the day, which is unusual for many mosquito species. Aedes albopictus is a vector for dengue, chikungunya, and Zika viruses, making it a concern for urban and suburban environments. It prefers small, stagnant water containers like buckets, flower pots, and bird baths for laying eggs. Despite its dangerous reputation, it also plays a role in local food chains, serving as prey for birds, frogs, and insects. Identifying Aedes albopictus in the wild is facilitated by its distinctive coloration and daytime activity. Controlling its population often involves habitat removal and careful monitoring of breeding sites.

3. Aedes aegypti (Yellow Fever Mosquito)

Aedes aegypti is one of the most medically significant mosquitoes in the world. Recognizable by its white markings on a dark body, it is the primary vector for yellow fever, dengue, chikungunya, and Zika viruses. Native to Africa, it has spread worldwide in tropical and subtropical regions. Unlike many mosquito species, Aedes aegypti prefers urban environments, often breeding in artificial containers like discarded tires and water storage tanks. The females are highly anthropophilic, meaning they actively seek human blood, which increases the risk of disease transmission. Their biting behavior often involves multiple hosts in a single feeding cycle. Despite this, Aedes aegypti is fascinating for entomologists due to its adaptability to human-altered environments. Understanding its habits and life cycle is essential for controlling mosquito-borne diseases and implementing effective public health campaigns.

4. Aedes japonicus (Asian Bush Mosquito)

Aedes japonicus, commonly known as the Asian Bush Mosquito, is an invasive species that has spread from Asia to North America and Europe. It is characterized by brownish-grey bodies with white stripes on its legs and thorax. This species prefers shaded, vegetated areas near small water collections such as tree holes, rock pools, and artificial containers. While not as dangerous as Aedes aegypti or albopictus, Aedes japonicus can transmit West Nile Virus and Japanese Encephalitis. Its cold tolerance allows it to survive in temperate climates, which gives it an advantage over other mosquito species. Observing Aedes japonicus can be challenging because it tends to be active during dawn and dusk. Researchers are particularly interested in this species because of its invasive nature and potential role in disease ecology. Managing its populations involves habitat control and monitoring of breeding areas to prevent local establishment.

5. Aedes vexans (Floodwater Mosquito)

Aedes vexans, or the Floodwater Mosquito, is widespread in temperate and subtropical regions around the world. True to its name, it prefers temporary pools of water formed after heavy rains for egg-laying. Adults are medium-sized, brownish mosquitoes with subtle white markings. They are notorious for their aggressive biting behavior, especially at dusk and dawn. Although not a primary vector for major diseases like malaria, Aedes vexans can transmit certain viruses, including West Nile Virus and California Encephalitis. Their population numbers can surge after flooding events, leading to significant nuisance and potential public health concerns. Ecologically, Aedes vexans plays a role as prey for birds, bats, and predatory insects, highlighting its importance in the food web. Observing this species provides insights into floodplain ecology and mosquito population dynamics.

These first five mosquitoes highlight the diversity of habits, appearances, and risks associated with the types of mosquitos. From the malaria-carrying Anopheles gambiae to the invasive Aedes japonicus, each species has adapted uniquely to its environment, showing both the resilience and ecological significance of mosquitoes in nature.

6. Aedes triseriatus (Tree Hole Mosquito)

Aedes triseriatus, commonly called the Tree Hole Mosquito, is a species widely found in North America. As the name suggests, it breeds in natural containers like tree holes, water-filled cavities, and occasionally artificial containers mimicking such habitats. This mosquito is a primary vector for La Crosse Encephalitis, a rare but serious disease affecting humans. Females have dark bodies with white markings, particularly on their legs, which helps distinguish them from other Aedes species. Active mostly during the day, they are persistent biters, often targeting humans and small mammals. Studying their life cycle reveals how their eggs can survive dry periods and hatch when water returns, showing impressive adaptation to fluctuating environments. Ecologically, Aedes triseriatus contributes to food webs, serving as prey for birds, bats, and aquatic predators during larval stages. Understanding this species aids in both mosquito control efforts and awareness of disease risk.

7. Culex quinquefasciatus (Southern House Mosquito)

Culex quinquefasciatus, also known as the Southern House Mosquito, is widespread in tropical and subtropical regions. Recognizable by its slender brownish body and pale banding on the abdomen, it often thrives around human settlements. This species is a known vector for West Nile Virus, filariasis, and St. Louis Encephalitis. Females lay eggs in stagnant water containing organic material, such as sewage ditches, storm drains, and unclean containers. They feed primarily at night, making them less noticeable during the day but active in residential areas during evening hours. Their adaptability to urban environments makes them a challenge for public health agencies. Observing Culex quinquefasciatus in the wild reveals its nocturnal habits and its ability to take multiple blood meals per reproductive cycle, which increases disease transmission risk. Controlling populations often involves proper water management and eliminating breeding habitats.

8. Culex pipiens (Common House Mosquito)

Culex pipiens, known as the Common House Mosquito, is one of the most familiar mosquitoes in temperate regions. With a dull brown color and subtle pale markings, it is less visually striking than its Aedes counterparts but equally important from a public health perspective. This species can transmit West Nile Virus, filarial worms, and other viral diseases. They prefer to breed in standing water near human habitats, such as gutters, birdbaths, and containers. Unlike some day-active mosquitoes, Culex pipiens is nocturnal, primarily feeding during the night. Their reproductive cycle allows rapid population growth in favorable conditions, particularly warm and humid environments. Studying this mosquito gives insight into urban mosquito ecology, demonstrating how human activity inadvertently supports their survival. Despite being a nuisance, they are also a food source for nocturnal predators like bats and some birds, emphasizing their ecological role.

9. Culex tarsalis (Western Encephalitis Mosquito)

10. Coquillettidia perturbans

Coquillettidia perturbans is a fascinating species known as the Cattail Mosquito. Found in North America, they exhibit a unique larval adaptation: they attach to submerged plant roots to obtain oxygen, allowing them to survive in low-oxygen waters that other species cannot inhabit. Adults are medium-sized and dark with lighter scales on the thorax and legs. They are vectors for Eastern Equine Encephalitis and can transmit other arboviruses. This species prefers marshes and wetlands, making them less common in urban areas but potentially abundant in rural wetlands. Their life cycle demonstrates remarkable adaptation to aquatic environments, and their presence indicates healthy wetland ecosystems. Although a threat to humans and livestock due to their biting habits, they also play a role in aquatic food chains, supporting birds, amphibians, and predatory insects.

These next five mosquitoes (#6–#10) illustrate the diversity of habitats, feeding behaviors, and disease relevance among types of mosquitos. From the tree-hole specialist Aedes triseriatus to the wetland-adapted Coquillettidia perturbans, each species highlights the intricate balance between ecological function and public health concern.

11. Culiseta melanura (Black-Tailed Mosquito)

Culiseta melanura, commonly called the Black-Tailed Mosquito, is primarily found in the wetlands and swampy areas of eastern North America. Its larvae prefer cryptic habitats such as the water-filled roots of sphagnum moss, which helps them avoid predators. Adults are slender, dark-colored mosquitoes with distinctive black-tipped abdomens. Culiseta melanura is a key vector for the Eastern Equine Encephalitis virus, transmitting it primarily among bird populations. Humans are usually incidental hosts, but their presence near wetland areas can increase the risk of infection. Observing these mosquitoes is challenging due to their preference for secluded habitats, but they are fascinating examples of adaptation in mosquito species. They also contribute to local food webs, serving as prey for dragonflies, frogs, and birds, highlighting their ecological role.

12. Psorophora ciliata

Psorophora ciliata, known as the Gallinipper or Big-Eared Mosquito, is among the largest mosquito species in North America. Adults have striking black-and-white patterns and can deliver painful bites due to their size and robust proboscis. This species breeds in temporary floodwater pools, ditches, and depressions that fill after heavy rainfall. Psorophora ciliata is capable of transmitting certain arboviruses, although it is less significant medically than other Aedes or Anopheles species. Their larvae are predatory and feed on other mosquito larvae, which can influence local mosquito populations. Fascinatingly, these mosquitoes can survive long periods as eggs during dry conditions, ready to hatch when water returns. Observing Psorophora ciliata offers insight into the balance of predator and prey in aquatic microhabitats, highlighting both nuisance and ecological value.

13. Mansonia uniformis

Mansonia uniformis is a tropical and subtropical mosquito species known for its unusual larval adaptation. Larvae attach to aquatic plants, extracting oxygen directly from the plant tissue, which allows them to survive in low-oxygen waters unsuitable for other species. Adults are medium-sized with brownish bodies and faint markings. They are vectors of filarial parasites and can contribute to the spread of certain arboviruses. Breeding in permanent swamps and marshes, Mansonia uniformis demonstrates how specialized adaptations enable mosquitoes to occupy unique ecological niches. Studying this species reveals the interplay between wetland health, plant availability, and mosquito survival, emphasizing the importance of habitat conservation alongside public health monitoring. Although they bite humans, they are generally less aggressive than Aedes species, providing a different ecological perspective on mosquito behavior.

14. Psorophora ferox

Psorophora ferox, sometimes called the Fierce Mosquito, inhabits North and South America. Adults are dark brown with lighter markings on the thorax and legs. Their larvae thrive in temporary floodwaters, including puddles and forest depressions. Psorophora ferox is aggressive and capable of multiple bites in a single feeding session. While not a major vector of human disease, they can carry arboviruses in certain regions. Their rapid population growth after rainfall events can make them a local nuisance. Ecologically, Psorophora ferox larvae help recycle organic material in flooded habitats, while adults serve as prey for birds, bats, and predatory insects. This species exemplifies how mosquitoes adapt to ephemeral water bodies, balancing nuisance factors with ecological contribution.

15. Psorophora howardii

Psorophora howardii is another large mosquito species in North America, closely related to Psorophora ferox. Adults have striking black and yellow patterns, with robust proboscises that deliver painful bites. Larvae develop in floodwater pools, ditches, and ephemeral ponds, often emerging in synchrony after rain events. This species is aggressive but plays a role in controlling other mosquito populations through predatory larval behavior. While not a primary vector for major human diseases, it can carry arboviruses locally. Observing Psorophora howardii highlights the ecological dynamics of floodwater mosquitoes, including competition, predation, and adaptation to temporary habitats. Their presence demonstrates how environmental conditions shape mosquito populations and behavior.

16. Toxorhynchites rutilus (Predatory Mosquito)

Toxorhynchites rutilus is unique among mosquitoes because adults do not feed on blood. Instead, they feed on nectar, making them harmless to humans. Larvae are predatory, consuming other mosquito larvae in containers, tree holes, and small pools. Adults are large, with iridescent wings and distinct body markings. Toxorhynchites rutilus is important for natural mosquito control and demonstrates the diversity of feeding strategies within mosquito species. Studying them provides insight into integrated pest management, as their presence reduces populations of blood-feeding species. They are active during the day and are less aggressive, which makes them an interesting species for ecological study and education about predator-prey relationships among mosquitoes.

17. Anopheles stephensi

Anopheles stephensi is a significant malaria vector found in South Asia and parts of the Middle East. Adults are slender mosquitoes with spotted wings and an angled resting posture typical of Anopheles species. They prefer urban and peri-urban habitats, breeding in man-made water containers like cisterns, wells, and barrels. Females feed primarily on humans, making them efficient vectors of malaria. Their nocturnal feeding habits, coupled with adaptability to human environments, pose challenges for malaria control. Studying Anopheles stephensi offers insights into urban vector ecology, the interaction of mosquitoes with human settlements, and effective disease prevention strategies. They are integral to understanding malaria epidemiology in affected regions.

18. Anopheles funestus

Anopheles funestus is another major malaria vector in Africa. Adults have long legs, slender bodies, and distinctive spotted wings. They breed in permanent or semi-permanent freshwater habitats such as ponds, swamps, and slow-moving streams. Females feed at night and prefer humans over animals, which contributes to high malaria transmission rates in affected areas. Their life cycle and habitat preferences highlight the importance of targeted interventions, such as indoor residual spraying and larval source management. Observing Anopheles funestus provides a window into the adaptation of mosquitoes to both natural and human-altered environments, emphasizing the intersection of ecology, public health, and human behavior.

19. Anopheles quadrimaculatus

Anopheles quadrimaculatus is a primary malaria vector in the eastern United States. Adults are brown with four dark spots on their wings, a feature referenced in the species name. They breed in freshwater habitats such as swamps, marshes, and slow streams. Females feed primarily at night on mammals, including humans. While malaria is largely controlled in the U.S., this species remains a model for studying mosquito ecology, vector behavior, and disease dynamics. Its presence demonstrates the potential for re-emergence of diseases if environmental and social conditions change. Ecologically, Anopheles quadrimaculatus larvae contribute to nutrient cycling in aquatic habitats and serve as prey for fish and invertebrates.

20. Anopheles dirus

Anopheles dirus is a highly efficient malaria vector in Southeast Asia, favoring forested and rural habitats. Adults are slender, with spotted wings and nocturnal feeding behavior. Females primarily feed on humans, which increases their role in malaria transmission. Larvae are typically found in shaded, temporary pools in forests. This species is notable for its ability to persist in diverse microhabitats and adapt to changes in water availability. Studying Anopheles dirus provides valuable lessons in vector ecology, forest mosquito behavior, and public health risk management. Their ecological contribution includes serving as prey for a range of predators, maintaining the balance of forest aquatic ecosystems.

These ten mosquitoes (#11–#20) illustrate the incredible diversity of types of mosquitos. From predatory Toxorhynchites rutilus to deadly malaria vectors like Anopheles dirus, each species has adapted uniquely to its environment, highlighting the intersection of ecological function, human impact, and public health.

21. Anopheles arabiensis

Anopheles arabiensis is a major malaria vector in Africa, particularly in arid and semi-arid regions. Adults have the characteristic Anopheles posture with spotted wings and a slender body. They breed in small, sunlit pools, rice paddies, and temporary water collections. Unlike some Anopheles species, Anopheles arabiensis displays both indoor and outdoor feeding behavior, making control more challenging. Females prefer human blood but will feed on animals when humans are scarce. Their nocturnal feeding habits coincide with peak malaria transmission times. Studying Anopheles arabiensis provides critical insights into malaria epidemiology, vector behavior, and effective intervention strategies such as bed nets and larval habitat management. Ecologically, they are part of the food chain, supporting predators like dragonflies, frogs, and birds.

22. Anopheles albimanus

Anopheles albimanus is prevalent in Central and South America and is a significant malaria vector in these regions. Adults are medium-sized, brown mosquitoes with characteristic wing patterns. They prefer clean, sunlit water sources for breeding, such as ponds, marshes, and slow streams. Females feed primarily on humans, usually at night, making them efficient vectors. Their life cycle is highly influenced by environmental factors like rainfall and temperature, which affects malaria transmission seasonally. Observing Anopheles albimanus in the wild provides insights into vector ecology, breeding preferences, and human interaction with mosquito habitats. While they are a concern for public health, they also contribute to local ecosystems as prey for various predators.

23. Anopheles punctipennis

Anopheles punctipennis is native to North America and is recognized for its four dark spots on the wings, giving it its name. They breed in clean, permanent, or semi-permanent water sources, including marshes, ponds, and slow streams. Females feed on mammals, including humans, at night, and they are capable of transmitting certain arboviruses and malaria under experimental conditions. Their larvae play a role in aquatic ecosystems by consuming microorganisms and serving as prey for fish and aquatic insects. Studying Anopheles punctipennis offers an understanding of how temperate mosquitoes adapt to seasonal changes and the importance of wetland conservation in maintaining ecological balance.

24. Aedes scapularis

Aedes scapularis is found in Central and South America and is known for its dark brown body with subtle pale markings. It breeds in temporary water collections, often in rural or peri-urban environments. Females are aggressive day-biting mosquitoes and can transmit arboviruses such as yellow fever. This species’ adaptability to human-modified habitats highlights the interplay between mosquito ecology and human activity. Their larvae contribute to nutrient cycling in temporary water pools and serve as prey for predatory insects and amphibians. Observing Aedes scapularis provides insight into floodwater mosquito behavior, rapid population growth after rainfall, and strategies for minimizing human-mosquito contact.

25. Ochlerotatus triseriatus (Eastern Tree Hole Mosquito)

Ochlerotatus triseriatus, also called the Eastern Tree Hole Mosquito, is a vector of La Crosse Encephalitis in North America. Adults have dark brown bodies with white bands on their legs. They prefer breeding in natural containers such as tree holes, but also use artificial containers that mimic these habitats. This species is active during the day, often biting humans in shaded areas. Their eggs can survive dry periods, hatching when water returns, demonstrating remarkable adaptation to fluctuating environments. Observing Ochlerotatus triseriatus helps understand the ecology of container-breeding mosquitoes and highlights the importance of managing artificial breeding sites to reduce disease risk. Ecologically, they serve as prey for birds, dragonflies, and aquatic predators during the larval stage.

26. Aedes sticticus

Aedes sticticus, commonly called the Floodwater Mosquito, is native to North America and Europe. Adults are large, dark mosquitoes with lighter markings on the thorax and legs. They breed in temporary floodwaters along riverbanks and low-lying fields. Females are aggressive biters and can deliver multiple bites in a single feeding session. While not a major vector of human disease, they are capable of transmitting certain arboviruses locally. Their larvae play a role in floodplain nutrient cycling, and adults serve as prey for birds and bats. Observing Aedes sticticus demonstrates how mosquitoes adapt to ephemeral habitats, surviving in conditions that other species cannot, and highlights the challenges of floodwater mosquito management in affected regions.

27. Aedes togoi

Aedes togoi, also called the Coastal Rock Pool Mosquito, is found in Asia and parts of the Pacific. It is recognized by its dark body with light bands on the legs and thorax. This species breeds in coastal rock pools and brackish water environments, an unusual habitat compared to most container-breeding mosquitoes. Females are day-active and bite humans and other mammals. Aedes togoi can transmit Japanese Encephalitis and other arboviruses. Studying this species offers insight into mosquito adaptation to saline and semi-saline environments, as well as the interaction of mosquitoes with coastal ecosystems. They also serve as prey for coastal birds and predatory insects, integrating into the local food web.

28. Culex mimulus

Culex mimulus is a mosquito species found in North and Central America. Adults are small to medium-sized with subtle pale markings on the legs and thorax. They breed in stagnant freshwater, such as ditches, pools, and artificial containers. Females are nocturnal feeders and can transmit arboviruses, although they are less significant medically than other Culex species. Larvae contribute to nutrient cycling in aquatic habitats and serve as prey for fish and other aquatic organisms. Observing Culex mimulus provides understanding of mosquito ecology in rural and suburban habitats, emphasizing the importance of managing stagnant water to reduce mosquito populations and disease risk.

29. Culex nigripalpus

Culex nigripalpus is native to the southeastern United States and parts of Central America. Adults are brown with subtle light markings, and females are primarily nocturnal feeders. They are vectors for St. Louis Encephalitis and West Nile Virus. Breeding occurs in stagnant freshwater bodies rich in organic material. Their larvae play a role in aquatic ecosystems by consuming microorganisms and serving as prey for fish and predatory insects. Understanding Culex nigripalpus behavior, breeding preferences, and vector potential is essential for managing mosquito-borne diseases and protecting human health in affected regions.

30. Culex salinarius

Culex salinarius is found along the Atlantic coast of North America and other temperate regions. Adults are medium-sized with brownish bodies and light markings. They breed in brackish or saltwater pools, salt marshes, and coastal ponds. Females feed on mammals, including humans, and are vectors for Eastern Equine Encephalitis and West Nile Virus. Their larvae play an important role in coastal ecosystems, recycling nutrients and providing food for predators like fish, birds, and predatory insects. Observing Culex salinarius highlights how mosquito species adapt to saline habitats while maintaining ecological importance and public health relevance.

These ten mosquitoes (#21–#30) illustrate the diversity in habitat preference, feeding behavior, and disease relevance among types of mosquitos. From urban-adapted Anopheles arabiensis to coastal specialists like Culex salinarius, each species showcases unique adaptations that balance ecological function with public health challenges.

31. Culex restuans

Culex restuans is a common mosquito in North America, particularly in urban and suburban areas. Adults are brown with faint pale markings on the legs and thorax. They breed in stagnant water such as rain-filled containers, ditches, and storm drains. Females feed at night on mammals and are significant vectors for West Nile Virus. Their larvae contribute to aquatic ecosystems by consuming microorganisms and serving as prey for fish and predatory insects. Studying Culex restuans helps understand urban mosquito ecology and the seasonal dynamics of disease transmission, especially during warm months when populations peak.

32. Culex territans

Culex territans is a mosquito species found across North America and Europe. Unlike many Culex species, they primarily feed on amphibians, including frogs and salamanders, rather than mammals. Adults are small and brown, with subtle pale markings. Breeding occurs in permanent or temporary freshwater pools. This species plays an important ecological role, linking mosquito populations to amphibian health and ecosystem balance. While not a major human disease vector, their interactions with wildlife provide insights into ecological networks and mosquito adaptation to specialized feeding habits.

33. Uranotaenia sapphirina

Uranotaenia sapphirina is a small mosquito found in North America, known for its bright metallic blue or green sheen. It feeds primarily on amphibians and reptiles, rarely biting humans. They breed in shallow, vegetated freshwater pools such as ponds and marshes. Although not medically significant to humans, Uranotaenia sapphirina larvae are important components of aquatic food webs, recycling nutrients and serving as prey for predatory insects and fish. Observing this species provides an example of specialized feeding behavior and adaptation to natural habitats, highlighting the diversity of mosquito ecological niches.

34. Deinocerites cancer (Crabhole Mosquito)

Deinocerites cancer, commonly called the Crabhole Mosquito, is found in coastal regions of North and Central America. Adults are medium-sized with dark brown bodies and lighter markings on the thorax. They breed in burrows of land crabs and other coastal invertebrates, making them highly specialized. Females feed on birds and mammals near coastal areas and can be vectors for arboviruses. Their unique breeding habits show remarkable adaptation to coastal ecosystems, demonstrating how mosquitoes exploit specialized habitats. Studying Deinocerites cancer helps understand species interactions and the ecological significance of coastal mosquito populations.

35. Orthopodomyia signifera

Orthopodomyia signifera is a mosquito species found in North America and the Caribbean. Adults are medium-sized with brownish bodies and subtle pale markings. They breed in water-filled tree holes and containers with clean water. Females feed primarily on birds and occasionally mammals. While not a major human disease vector, Orthopodomyia signifera plays a key role in wetland and forest ecosystems, with larvae contributing to nutrient cycling and adults serving as prey for birds and bats. Studying this species highlights how forest mosquitoes maintain ecological balance while rarely affecting humans directly.

36. Ochlerotatus atropalpus

Ochlerotatus atropalpus, also called the Winter Pool Mosquito, is found in North America. Adults are small to medium-sized with dark bodies and pale markings on the legs. They breed in temporary pools formed by rain or snowmelt and are aggressive day-biting mosquitoes. Females feed on humans and mammals, although they are less medically important than other Aedes species. Their larvae play an important role in recycling organic matter in temporary aquatic habitats, and adults serve as prey for birds, amphibians, and predatory insects. Observing Ochlerotatus atropalpus provides insight into ephemeral water mosquito ecology and population dynamics.

37. Ochlerotatus cantator

Ochlerotatus cantator is found in North America, particularly in coastal marshes and floodplains. Adults have dark bodies with subtle light markings and are active during the day. Females are aggressive biters and can carry arboviruses, although human infection risk is relatively low. Breeding occurs in brackish water pools and marsh depressions. Larvae recycle nutrients in these aquatic habitats and provide food for predatory insects and fish. Studying Ochlerotatus cantator demonstrates the interaction between coastal ecosystems, mosquito adaptation, and the balance between nuisance and ecological function.

38. Ochlerotatus canadensis

Ochlerotatus canadensis, also called the Canadian Mosquito, is common in northern North America. Adults are small, brown mosquitoes with pale leg bands. They breed in floodwater areas, temporary pools, and boggy depressions. Females are aggressive daytime feeders, primarily targeting humans and large mammals. Larvae contribute to nutrient cycling in temporary aquatic habitats, while adults are prey for birds and predatory insects. This species highlights how northern mosquitoes adapt to seasonal climates, with populations peaking during warmer months and declining in winter. Understanding Ochlerotatus canadensis provides insight into mosquito population cycles in temperate regions.

39. Ochlerotatus sticticus

Ochlerotatus sticticus, commonly called the Floodwater Mosquito, is found across North America and Europe. Adults are medium-sized with dark bodies and faint pale markings. They breed in temporary floodwater pools, riverbanks, and low-lying fields. Females are aggressive biters and may deliver multiple bites. While not a major disease vector, they can transmit arboviruses locally. Larvae play an important role in floodplain ecosystems by recycling nutrients and serving as food for predators. Observing Ochlerotatus sticticus highlights adaptation to ephemeral habitats and the importance of temporary water sources in mosquito ecology.

40. Wyeomyia smithii

Wyeomyia smithii, commonly called the Pitcher Plant Mosquito, is unique in its habitat preference. Larvae develop exclusively in the water-filled leaves of pitcher plants in bogs and wetlands of North America. Adults are small, dark mosquitoes that rarely bite humans, feeding primarily on nectar. This species is ecologically important as it completes its life cycle within the pitcher plant, influencing the plant’s microecosystem by controlling prey populations. Studying Wyeomyia smithii provides insight into highly specialized mosquito adaptations and the delicate balance of wetland ecosystems. They exemplify how mosquitoes can occupy niche habitats while playing integral ecological roles.

Conclusion

The world of mosquitoes is far more diverse than most people realize. Across these 40 species, we see incredible variation in size, habitat, feeding habits, and ecological roles. From aggressive day-biting Aedes species to predatory Toxorhynchites and specialized Wyeomyia smithii living in pitcher plants, each mosquito has adapted uniquely to its environment. Understanding types of mosquitos is not just about knowing which ones bite humans or carry diseases—it’s also about appreciating their roles in ecosystems, from nutrient cycling in aquatic habitats to serving as prey for birds, fish, and insects. By learning about these mosquitoes, we can better manage public health risks, protect habitats, and even harness natural predators for control. Observing these fascinating insects reminds us of the delicate balance between humans and the tiny creatures that share our world. Whether for education, research, or conservation, knowing the diversity of mosquitos helps us make informed decisions and coexist more safely with these complex and often misunderstood insects.

Frequently Asked Questions about Types of Mosquitos

1. What are the main types of mosquitos?

The main types include Aedes, Anopheles, Culex, Ochlerotatus, Wyeomyia, and Toxorhynchites, each with distinct habitats and behaviors.

2. Which mosquito species bite humans the most?

Species like Aedes aegypti, Aedes albopictus, and Culex quinquefasciatus are known for aggressive human biting.

3. Are all mosquitos dangerous to humans?

No, not all mosquitos transmit diseases. Many species only feed on birds, amphibians, or other animals.

4. How do mosquitoes spread diseases?

Female mosquitoes transmit pathogens like viruses and parasites when they bite infected hosts and then bite humans or animals.

5. What diseases do Anopheles mosquitoes carry?

Anopheles mosquitoes are primary vectors for malaria and can also transmit some arboviruses.

6. What is the difference between Aedes and Culex mosquitoes?

Aedes mosquitoes often bite during the day and are vectors for dengue and Zika, while Culex bite at night and can spread West Nile Virus.

7. Which mosquitoes live in coastal areas?

Species like Deinocerites cancer and Culex salinarius thrive in coastal marshes, brackish water, and crabhole habitats.

8. What habitats do mosquito larvae prefer?

Larvae are found in stagnant water: ponds, marshes, floodplains, tree holes, artificial containers, and even pitcher plants.

9. Can mosquitos live in saltwater?

Some species, like Culex salinarius, can develop in brackish or saltwater environments, showing remarkable adaptability.

10. Are all mosquito larvae harmful?

No, mosquito larvae are important for aquatic ecosystems, recycling nutrients and serving as prey for fish and insects.

11. What is the lifespan of a mosquito?

Adult mosquitoes usually live 2–4 weeks, although some species like Wyeomyia smithii may have shorter or longer lifespans depending on habitat.

12. Why do only female mosquitoes bite?

Females require blood for egg development, while males feed on nectar and plant juices.

13. How can mosquito breeding be controlled?

Removing standing water, using larvicides, introducing natural predators, and mosquito nets are effective control methods.

14. Are all Aedes mosquitoes day-biters?

Most Aedes species, such as Aedes aegypti and Aedes scapularis, are active during the day, increasing human exposure.

15. Can mosquitoes live in cold climates?

Species like Ochlerotatus canadensis survive seasonal climates by overwintering in the egg stage.

16. Which mosquito spreads La Crosse Encephalitis?

Ochlerotatus triseriatus, the Eastern Tree Hole Mosquito, is the primary vector for La Crosse Encephalitis.

17. Do mosquitoes eat anything besides blood?

Yes, both males and some females feed on nectar, plant juices, and other sugar sources for energy.

18. Can mosquitoes transmit West Nile Virus?

Culex species, including Culex pipiens, Culex quinquefasciatus, and Culex restuans, are known vectors for West Nile Virus.

19. What is a floodwater mosquito?

Floodwater mosquitoes, like Aedes sticticus and Ochlerotatus sticticus, breed in temporary pools created by rainfall or floods.

20. How do mosquitoes survive dry conditions?

Some species, such as Ochlerotatus atropalpus, lay drought-resistant eggs that hatch when water returns.

21. Can mosquito bites cause allergic reactions?

Yes, bites can cause itching, redness, swelling, and in rare cases, more severe allergic responses.

22. What predators eat mosquitoes?

Birds, bats, frogs, dragonflies, fish, and other insects feed on mosquito larvae and adults, keeping populations in check.

23. Do mosquito species differ in flight range?

Yes, some species travel only a few hundred meters, while others, like Anopheles, may fly several kilometers in search of hosts.

24. Which mosquito is called the ‘Crabhole Mosquito’?

Deinocerites cancer breeds in crab burrows and coastal habitats, making it highly specialized.

25. How can you identify mosquito species?

Identification involves examining wing patterns, body coloration, leg markings, and habitat preference.

26. Are mosquitoes important for ecosystems?

Yes, they recycle nutrients, serve as food for predators, and influence ecological balance in aquatic and terrestrial environments.

27. Which mosquito lives in pitcher plants?

Wyeomyia smithii completes its entire larval development in the water-filled leaves of pitcher plants.

28. How do mosquitoes contribute to disease outbreaks?

By feeding on infected hosts and then biting humans or animals, mosquitoes transmit viruses and parasites like malaria, dengue, and Zika.

29. What is a night-biting mosquito?

Culex species and many Anopheles mosquitoes are primarily active at night, reducing human detection.

30. Which mosquitoes are aggressive daytime biters?

Aedes aegypti, Aedes albopictus, and Aedes scapularis are known for biting humans actively during the day.

31. Can mosquitoes live in artificial containers?

Yes, many species, especially Aedes and Ochlerotatus, breed in buckets, tires, plant pots, and other man-made containers.

32. Which mosquito is associated with Japanese Encephalitis?

Aedes togoi and some Culex species can transmit Japanese Encephalitis in Asia and the Pacific.

33. How fast do mosquitoes reproduce?

Female mosquitoes can lay hundreds of eggs in a single cycle, often hatching within days in suitable water conditions.

34. Are all mosquito larvae aquatic?

Yes, all mosquito larvae develop in water, from temporary puddles to permanent ponds, before emerging as adults.

35. How long does a mosquito egg last?

Egg longevity varies by species; some drought-resistant eggs can survive months before hatching.

36. Can mosquitoes adapt to new environments?

Yes, species like Aedes albopictus have expanded globally by adapting to urban and suburban habitats.

37. Do all mosquito species bite humans?

No, many species feed on birds, amphibians, or reptiles and rarely interact with humans.

38. Which mosquito transmits Eastern Equine Encephalitis?

Culex salinarius is one of the main vectors for Eastern Equine Encephalitis in coastal regions.

39. Can mosquito larvae survive in polluted water?

Some species tolerate moderately polluted water, but many prefer clean or slightly organic-rich habitats.

40. How can humans reduce mosquito populations?

Eliminate standing water, use protective clothing, apply repellents, and encourage natural predators to reduce mosquito numbers safely.

41. Why are mosquitoes considered ecological indicators?

Mosquito presence and diversity can indicate water quality, habitat health, and changes in local ecosystems.

42. Are all mosquito-borne diseases fatal?

No, many mosquito-borne diseases cause mild symptoms, but some, like malaria or West Nile Virus, can be severe if untreated.

43. Do mosquitoes have natural enemies?

Yes, numerous predators including fish, birds, bats, dragonflies, and predatory insects help control mosquito populations.

44. How do mosquito populations change seasonally?

Many species, like Ochlerotatus canadensis, peak in summer and decline in winter, while tropical species may breed year-round.

45. Can mosquitoes survive indoors?

Some species, such as Culex and Aedes aegypti, can live and breed indoors if water sources are available.

Read more: 15 Types of Reindeer (Pictures And Identification)