Tuna are among the most recognizable fish on the planet, and people often picture them slicing through open water with strong, steady movements. This guide highlights 25 Types of Tuna from different oceans, giving readers a clear look at how these fish live, feed, and survive in deep blue habitats. If you’re curious about how each species stands apart—whether in speed, size, or behavior—this article covers the essentials in a simple and friendly way. Many of these tuna play important roles in marine ecosystems, helping maintain balance in waters that stretch across the globe. The information here is written for beginners, hobbyists, and anyone who enjoys learning about wildlife. By the end, you’ll have a better sense of how these tuna compare and why each one matters. This introduction includes the keyword Types of Tuna to support search visibility while keeping the flow natural.

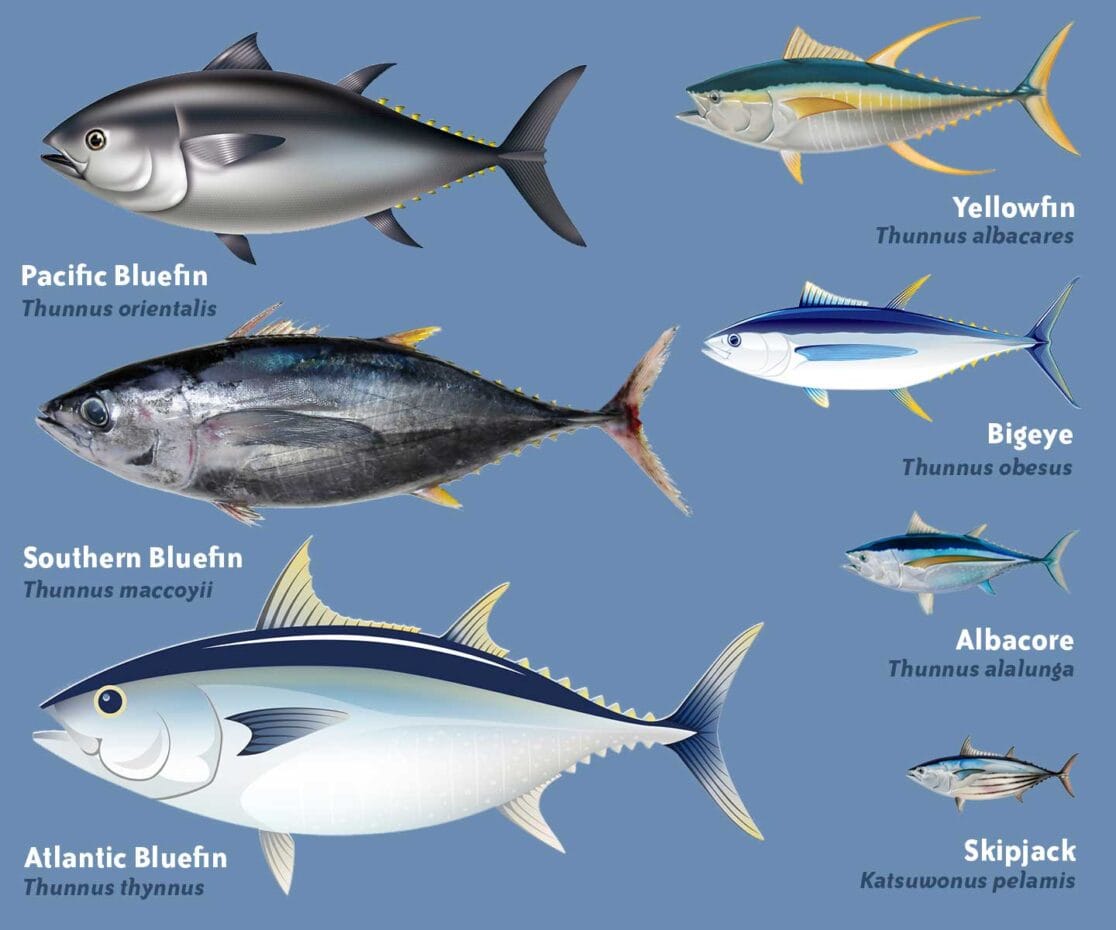

1. Atlantic Bluefin Tuna

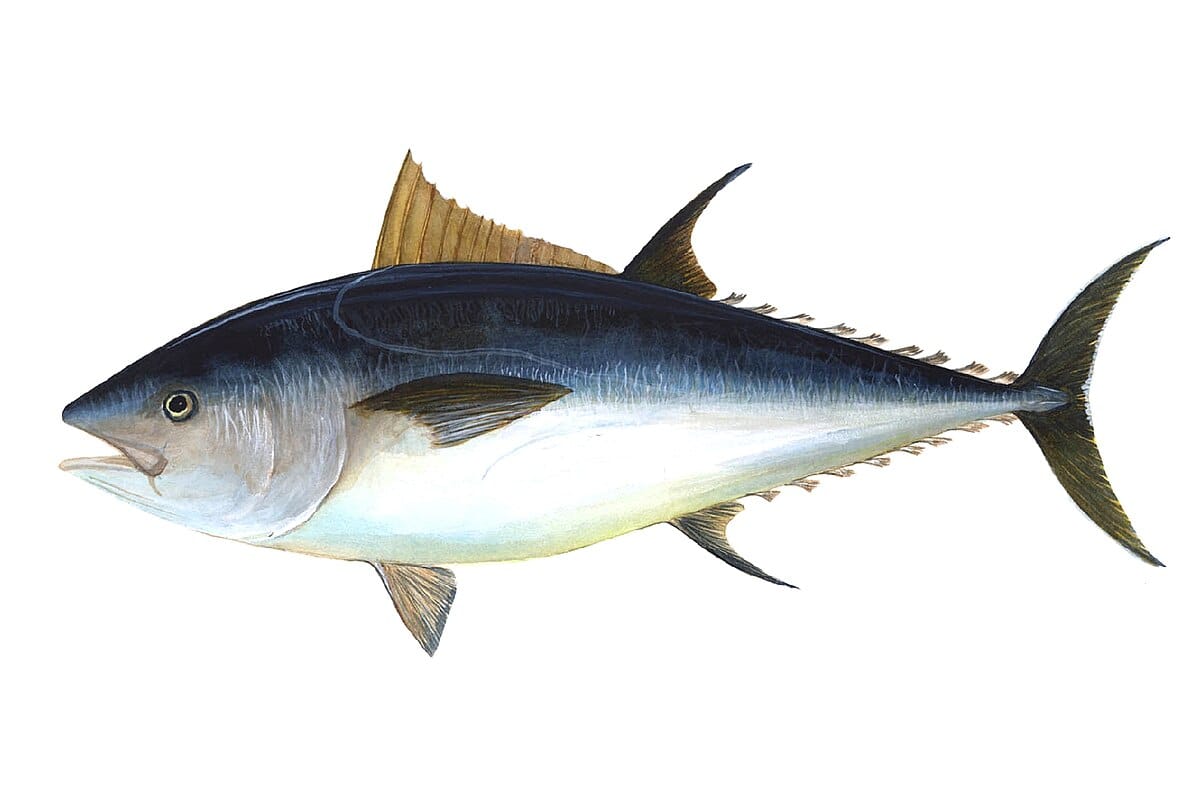

The Atlantic Bluefin Tuna is often described as one of the strongest fish in open water. Many people first hear about it through stories of impressive speed, and those stories are accurate. This species can push through rough currents with steady power, covering long distances during migration. What makes the Atlantic Bluefin so interesting is how its body works almost like a living engine. It keeps a higher internal temperature than the surrounding water, giving it more strength during long swims.

These tuna grow to remarkable sizes. Some individuals reach weights that surprise even researchers, and fishermen often share stories of challenging battles with them. Their deep blue coloring is one of the first things people notice. The back is dark, while the sides are lighter, reflecting the ocean in a way that helps them avoid predators and sneak up on prey. It’s a clever adaptation that works well in open water.

In terms of behavior, the Atlantic Bluefin tends to move in groups. This gives them better chances when hunting fast-moving prey like mackerel or squid. People sometimes compare these groups to coordinated teams, each fish adjusting its path in response to the others. The species uses powerful bursts of speed when feeding, and it can dive to significant depths when needed.

These tuna are well-known in the fishing industry. They have been targeted for many decades, and their value has created heavy pressure on populations. Conservation efforts today focus on keeping numbers steady and protecting breeding grounds. Many countries now follow strict rules to reduce overharvesting. Even with all the human interest surrounding them, the Atlantic Bluefin still moves with natural grace through the Atlantic, from the Gulf of Mexico to European waters.

Anyone reading about tuna for the first time often starts with this species, simply because it stands out. Its size, behavior, and role in the ocean give it a special place in marine biology discussions. And while it’s strongly associated with human fishing culture, the fish itself remains an impressive swimmer built for long distances and fast chases.

2. Pacific Bluefin Tuna

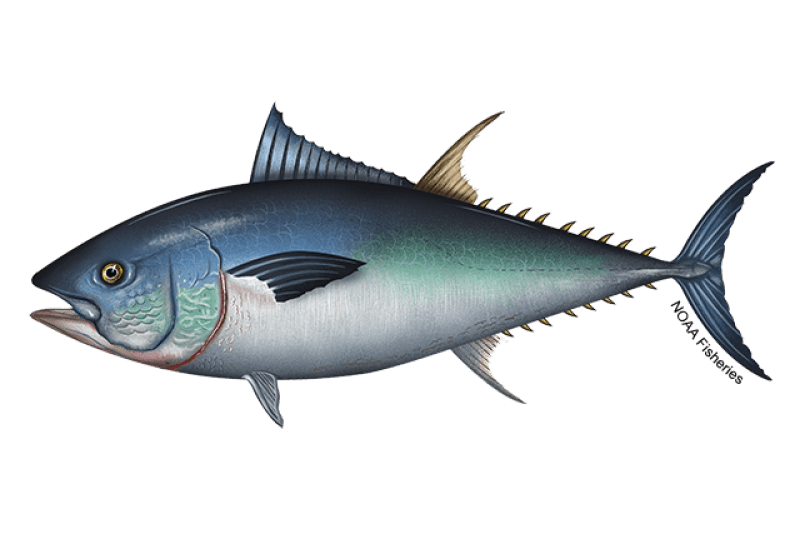

The Pacific Bluefin Tuna is another species many people recognize right away. It shares several traits with the Atlantic Bluefin, yet it has its own quirks that make it worth studying. One interesting detail is how early-life movements differ. Young Pacific Bluefin often travel long distances from western Pacific waters to the coast of North America before eventually returning. This round-trip behavior is something researchers track carefully.

The body shape is streamlined and dense, helping it cut through water with minimal resistance. People often say this tuna looks like a swimmer built for endurance. Its coloration is similar to that of its Atlantic relative: darker shades on the upper body, lighter on the underside. This contrast helps it blend in from multiple viewpoints, which is essential when avoiding large predators such as sharks.

Pacific Bluefin Tuna feed on a variety of prey, including anchovies, sardines, and squid. Because they travel so far, their diet shifts depending on the region and season. Their feeding behavior shows plenty of coordination, especially when hunting in groups. Some observers describe these feeding events as controlled chaos—rapid turns, quick chases, and sudden bursts of power.

Another important point about this species is its commercial value. It has been harvested in large numbers for many years, which led to declines in population size. Recent restrictions and monitoring help reduce pressure on the species, though the work is still ongoing. Many conservation groups watch the Pacific Bluefin carefully, as it’s considered an iconic animal in several parts of the Pacific region.

Even with these human influences, the Pacific Bluefin remains an impressive traveler. It can cover thousands of miles with steady determination. These long journeys tell scientists a lot about migration habits, breeding behavior, and how tuna respond to long-term environmental changes. When people talk about ocean giants with remarkable stamina, this species often makes the list.

3. Southern Bluefin Tuna

The Southern Bluefin Tuna spends most of its life in the cooler waters of the Southern Hemisphere. This species is known for its wide-ranging movements, traveling across ocean basins with surprising consistency. One reason it catches interest is its ability to handle colder water better than most tuna. The body retains warmth efficiently, allowing it to stay active even in lower temperatures.

In appearance, the Southern Bluefin looks somewhat like its relatives but still maintains its own character. Many individuals show a more rounded body shape with a distinct shine on the scales. As they grow larger, their movements become slower but more powerful. People sometimes describe adult Southern Bluefin as “steady cruisers,” because they move with deliberate, smooth motions.

This tuna eats fish, crustaceans, and cephalopods. Its feeding strategy is centered on bursts of speed followed by gliding motions that help it conserve energy. Group feeding is common, and the species often forms schools during certain stages of life. These schools can be impressive in size, giving the fish a better chance of finding food in open water.

The Southern Bluefin has faced significant conservation issues. Decades of heavy fishing led to noticeable population declines. International agreements now attempt to stabilize numbers by regulating catch limits. These rules help support long-term recovery but require strict cooperation between different countries. Despite these challenges, the species continues to roam vast areas of the ocean, relying on its strong muscles and steady swimming style.

People who study marine wildlife often talk about this species when discussing how certain fish handle cooler waters. The Southern Bluefin’s resilience makes it interesting from a biological perspective. Its long migrations also help scientists learn more about oceanic patterns, water temperatures, and how marine animals adapt over many years.

4. Yellowfin Tuna

Yellowfin Tuna stand out because of the bright yellow streaks along their fins. These markings catch the eye immediately, and they’re often the first clues that you’re looking at this species. Yellowfin live in tropical and subtropical waters, making them one of the more widespread tuna found worldwide. Their presence in warm regions gives them access to diverse food sources, from small fish to squid.

This species is shaped like a streamlined torpedo. The body is long, slender, and built for speed. Yellowfin can reach impressive velocities when chasing prey, and their sharp turns surprise many observers. If you’ve ever watched footage of tuna feeding near the surface, you may have seen Yellowfin darting in and out of baitfish schools.

Yellowfin Tuna are known for their cooperative hunting behavior. They often team up with dolphins or other large fish species. These mixed groups help confuse prey, increasing feeding success for everyone involved. The presence of dolphins does not mean the tuna rely on them, but the relationship is interesting enough that researchers study it regularly.

Compared to Bluefin species, Yellowfin grow quickly but do not reach the same heavyweight sizes. Even so, they’re still strong swimmers capable of long-distance travel. Their migration patterns cover wide ocean areas, and they often shift locations based on temperature changes and food availability.

Yellowfin Tuna are important in commercial fisheries. Many countries harvest them for food, and this demand keeps monitoring agencies busy. Efforts now focus on keeping fishing sustainable to prevent declines. Despite these concerns, the Yellowfin remains abundant in many regions, making it one of the most familiar tuna to both scientists and fishers.

5. Albacore Tuna

Albacore Tuna are sometimes called “white tuna” due to their lighter-colored flesh compared to other species. They’re smaller than Bluefin or Yellowfin, but they have their own appeal. These tuna travel widely across the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans. Their long, slender pectoral fins are one of the easiest identification features. When viewed from the side, these fins stretch farther back than many people expect.

The Albacore’s body is streamlined for extended swimming. It moves smoothly through open water and often forms large schools, especially during migration. These schools sometimes include individuals of similar age and size, making them easier to track for researchers studying population health.

Albacore feed on squid, crustaceans, and smaller fish. They hunt actively, often moving in zigzag patterns near the surface. Their feeding system relies on quick bursts of movement followed by steady glides. Many observers describe their swimming behavior as calm but purposeful.

Commercial fishing targets Albacore heavily, especially for canned products. This has created pressure on certain populations, though management plans aim to keep catch numbers sustainable. Many groups continue studying migration routes to better understand how to protect the species.

In appearance, Albacore are less flashy than Yellowfin, but their long fins and sleek movement give them a certain charm. People who enjoy learning about fish often appreciate this species for its wide distribution and interesting behavior. And while it may not be the largest tuna, it plays an important role in marine ecosystems around the world.

6. Bigeye Tuna

Bigeye Tuna is often admired by anglers and marine researchers because it carries several traits that make it stand out from other ocean wanderers. The species gets its name from—of course—its noticeably large eyes, which help it adapt to deep, dimly lit waters. While many tuna spend a considerable amount of time near the surface, Bigeye Tuna frequently dive several hundred meters in search of cooler temperatures and richer hunting grounds. This habit gives them access to prey that other tuna seldom reach, making them one of the more interesting fish for anyone who pays attention to underwater behavior.

Their appearance resembles Yellowfin Tuna at first glance, especially with the streamlined body and metallic sheen that catches the light. But closer observation reveals differences: the eyes are larger, the body is slightly more robust, and their finlets can shift between bright yellows and dusky browns depending on the light. Fishermen often point out that Bigeye Tuna feel heavier than expected for their length because of their dense muscle mass. These muscles aren’t just for speed—they help regulate temperature during deep dives, allowing them to shift between warm and cold waters without much trouble.

Bigeye Tuna generally roam tropical and subtropical oceans, forming loose schools that change location as food availability shifts. Their diet includes squid, crustaceans, lanternfish, and various pelagic species. Because they feed in deeper waters, scientists use special tagging devices to better understand their patterns. Some of these tags have revealed surprising vertical movements—one moment they’re cruising near the surface, and within minutes they plunge hundreds of meters as if chasing a mystery snack that darted below.

Commercially, Bigeye Tuna is prized for its firm, rich meat. It’s often used in sushi and sashimi, where the deeper red color tends to attract seafood enthusiasts. However, this popularity has led to management concerns. Many fisheries now emphasize responsible harvests to help maintain stable populations. Though Bigeye Tuna isn’t the fastest swimmer compared to others in the group, it compensates with exceptional endurance and a methodical way of moving through the ocean. If tuna species were runners, Bigeye would be the marathon athlete who keeps a steady pace rather than bursting ahead in short sprints.

Overall, Bigeye Tuna remains a fascinating species—adaptable, muscular, and somewhat secretive. Its ability to thrive at different depths, combined with its nutritional value, keeps it at the forefront of tuna discussions worldwide. Anyone exploring various Types of Tuna eventually encounters this species because it bridges the surface world with the darker, cooler layers far below.

7. Blackfin Tuna

Blackfin Tuna is the smallest of the true tuna group, but it has a reputation much larger than its size suggests. Found mainly in the western Atlantic—including the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea—this species thrives in warm, tropical water. Its most defining feature is the contrast between its deep-black dorsal area and the silvery-gray sides that shimmer when the fish turns in the light. Sometimes a golden streak appears along the body, as though Mother Nature added a stylish racing stripe just for fun.

Despite being smaller compared to Bluefin or Yellowfin Tuna, the Blackfin is a powerhouse in its own right. Anglers frequently describe it as “small but fiery,” thanks to its strong fight when hooked. Schools often gather near the surface, feeding aggressively on small fish and zooplankton. During feeding frenzies, they move in tight formations that create chaotic, bubbling patches on the surface—a sight that many fishermen consider a sign of a promising day.

Blackfin Tuna grow quickly, which helps them withstand fishing pressure better than slower-growing tuna. Most individuals weigh between 8 and 20 pounds, though larger ones make occasional appearances. Their streamlined shape allows them to dart through water with surprising speed, especially when they chase sardines, anchovies, or flying fish. The species also attracts dolphins and seabirds, creating a lively marine scene whenever prey becomes abundant.

From a culinary standpoint, Blackfin Tuna is appreciated for its mild flavor and versatility. It’s excellent grilled, seared, or served as poke. Because the flesh is lighter and softer compared to bigger ocean giants, chefs often prefer it for dishes that don’t require the intense richness of Bluefin or Bigeye. Many coastal communities celebrate Blackfin season with fishing tournaments that highlight both the sporting aspect and the cultural value of this vibrant species.

Although Blackfin Tuna doesn’t receive the same global spotlight as its larger relatives, it plays an important ecological role. Its fast reproduction, social schooling behavior, and reliance on surface waters make it an accessible species for scientists studying ocean productivity. Observing Blackfin patterns often gives insight into plankton blooms and seasonal changes in coastal ecosystems. In short, this small tuna is more significant than its size might imply, proving that even the “middleweight champions” of the sea deserve their moment of recognition.

8. Longtail Tuna

Longtail Tuna, sometimes called Northern Bluefin Tuna in local markets (not to be confused with the much larger Atlantic Bluefin), is common across the Indo-Pacific region. Its name refers to the elongated caudal peduncle—the narrow part leading to the tail—which gives the species a distinct silhouette. Though not as bulky as Yellowfin or Bigeye Tuna, it maintains a sturdy build and a metallic shine that shifts between deep blues and soft silvers depending on sunlight.

The species tends to inhabit coastal and offshore waters, usually near continental shelves. Longtail Tuna prefer warmer areas and are often found near surface currents where baitfish gather. Their diet consists largely of anchovies, sardines, mackerel fry, and squid. Because they feed close to the surface, fishermen sometimes spot them darting through schools of small fish, leaving behind splashes that sparkle like scattered coins in the water.

Longtail Tuna are speedy swimmers and are known for sudden, energetic bursts when they chase prey. While they do not reach the massive size of Bluefin or Bigeye, they can grow up to 40 inches in length. Their endurance makes them popular among recreational anglers, particularly in Australia and Southeast Asia. This species is often caught using trolling methods, and many fishing communities consider it a reliable target due to its availability throughout most of the year.

In local markets, Longtail Tuna is a staple. Its meat is moderately firm and has a clean flavor that works well in curries, grilled dishes, and lightly seared preparations. Unlike larger tuna species that sometimes develop a strong, fatty taste, Longtail Tuna offers balance—flavorful yet not overpowering. In many coastal households, it’s simply “the everyday tuna,” providing consistent nutrition and versatility at an accessible price.

Ecologically, Longtail Tuna contributes significantly to marine food webs. It occupies a mid-trophic role—both predator and prey—linking smaller fish populations with larger marine species such as sharks and large billfish. Scientists sometimes monitor Longtail Tuna schools to predict baitfish movements and seasonal changes in ocean temperature. This species also helps researchers assess how climate variations may influence tuna distribution patterns over time.

With its streamlined body, dependable presence near coastal waters, and cultural value throughout the Indo-Pacific, Longtail Tuna remains an essential species to include when discussing the many Types of Tuna worldwide.

9. Skipjack Tuna

Skipjack Tuna is one of the most recognizable species in global markets, primarily because it forms the backbone of the canned tuna industry. But judging Skipjack solely on that would be like assuming a skilled musician only plays background music—there’s more to this fish than a role in household pantries. Found in tropical and warm-temperate waters, Skipjack Tuna travel in enormous schools that sometimes include other tuna species, dolphins, or various pelagic fish.

The species has a compact, torpedo-shaped body with prominent horizontal stripes on the belly. These stripes become more visible after death, which is one reason fishers can identify them quickly. Skipjack are impressively fast swimmers, often reaching speeds that rival much larger tuna. Their constant motion helps them regulate temperature and maintain oxygen flow over their gills. If tuna species had a “most energetic” award, Skipjack would be a strong contender.

Skipjack feed primarily on small fish, crustaceans, and squid. Their feeding frenzies are dramatic—large schools churn the water, and seabirds swoop down to grab fleeing prey. Observing such activity feels like watching a perfectly timed ocean performance where everyone has a role. These feeding habits make Skipjack easier to locate, which contributes to their prominence in commercial fisheries.

Because Skipjack reproduce rapidly and grow quickly, they’re generally considered more resilient than slower-growing tuna. That said, responsible harvesting remains important as demand continues to rise. Many sustainability groups encourage purse-seine fishing methods that reduce bycatch, helping maintain healthy ecosystems.

Skipjack Tuna has a firm texture and mild flavor, which adapt well to grilling, searing, and pressure-cooking. In some regions, it’s eaten raw, though it’s less common in sushi compared to Yellowfin or Bluefin. Many coastal communities rely on Skipjack as a daily food source, using traditional recipes that have been passed down for generations.

Beyond its culinary and commercial value, Skipjack serves as a vital ecological species. It helps regulate populations of smaller fish and provides nourishment for sharks, billfish, and marine mammals. The sheer size of Skipjack schools plays an essential role in shaping predator–prey dynamics in warm oceans worldwide.

10. Little Tunny

Little Tunny—also known as False Albacore—is a small but feisty tuna commonly found in the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean. Although it’s not as sought after for culinary purposes, it’s one of the most beloved species among sport anglers because of its strength and speed. Hooking one feels like attaching the line to a fast-moving train; the moment it senses pressure, it shoots away with enough momentum to surprise even seasoned fishermen.

This species has a striking appearance: dark, wavy patterns on its back resemble brushstrokes, while a cluster of spots near the pectoral fin offers a reliable identification clue. The body shape is compact and muscular, showcasing the classic torpedo profile that all tuna share. Little Tunny often travel in lively schools that swim near the surface, especially when anchovies or sardines are abundant.

Little Tunny are opportunistic predators. They gorge on small fish, squid, and crustaceans, often pushing baitfish toward the surface in explosive bursts. Observers sometimes compare the sight to popcorn kernels erupting in hot oil—chaotic, rapid, and oddly mesmerizing. This behavior naturally attracts seabirds, dolphins, and larger fish, creating a buzzing feeding zone that anglers quickly recognize.

Although Little Tunny are edible, they have darker, oilier meat that isn’t as widely appreciated as other tuna. In many areas, they’re used for bait to target larger species. However, coastal families in parts of the Mediterranean prepare them in hearty stews or smoked specialties, showing that culinary preferences differ greatly across cultures.

From an ecological perspective, Little Tunny hold significant importance. They help control populations of smaller fish and supply food for larger predators. Their wide distribution and fast-paced lifestyle allow researchers to track environmental changes. For example, shifting Little Tunny patterns sometimes signal temperature changes or prey movement along coastlines.

Recreational anglers value this species for the thrill it brings. Stories circulate of rods bending to their limit and fishing reels buzzing like oversized insects. The fight is powerful relative to the fish’s size, making Little Tunny a favorite among those who enjoy fast, energetic battles on light tackle. Its speed, stamina, and flashy appearance make it a standout member of the broader tuna family, deserving recognition in any guide covering the Types of Tuna.

11. Bullet Tuna

Bullet Tuna gets its name from its compact, streamlined shape that resembles a polished projectile. This species thrives in warm, temperate waters across the Atlantic and Indo-Pacific, typically forming schools near the surface. Fishermen often spot them flashing just beneath breaking waves, darting through baitfish clusters with the speed and focus of a creature fully built for motion. Although small compared to big ocean heavyweights, Bullet Tuna delivers an impressive burst of agility that has made it a dependable catch for centuries.

Their bodies display dark blue coloration on the upper side, fading into silvery gray along the belly. Unlike many larger tuna, Bullet Tuna have subtle horizontal stripes near the flank. These patterns become more noticeable when the fish is in hand, making identification fairly simple once you know what to look for. Their dorsal fin sits low and backward, contributing to the bullet-like silhouette that makes them instantly recognizable.

Bullet Tuna prefer coastal zones, especially areas with strong currents or upwellings where plankton thrives. These nutrient-rich areas attract swarms of small fish and crustaceans—the perfect buffet for a schooling predator. When feeding, Bullet Tuna move as a coordinated group, slicing through baitballs in swift passes. Observing this synchronized behavior is a reminder of how tightly tuned their instincts are. One moment the ocean is calm; the next, silver flashes erupt as though someone flipped a switch.

This tuna species doesn’t usually exceed 16 inches in length, but what they lack in size they make up for in speed. Their rapid metabolism keeps them constantly moving, and their lean muscle helps them chase down agile prey. The meat is firm, mildly flavored, and commonly used in local markets across southern Europe and Asia. While Bullet Tuna rarely appears in upscale restaurants, it’s a household staple in traditional dishes—fried, grilled, or preserved.

Ecologically, Bullet Tuna plays a vital role by linking plankton-eating fish with larger marine predators. Larger tuna, seabirds, sharks, and dolphins all rely on these smaller species during seasonal feeding events. Because Bullet Tuna gathers near coastlines, scientists often track its movements to understand shifts in regional marine productivity.

Overall, Bullet Tuna is an excellent example of how smaller tuna species contribute to ocean dynamics. Its size may not impress trophy anglers, but its importance within coastal ecosystems and its cultural value across many fishing communities give it a well-earned place among the many Types of Tuna.

12. Frigate Tuna

Frigate Tuna, also called Auxis thazard, is a lively species commonly found across tropical and subtropical oceans. Its name reflects the resemblance to nimble frigate birds—both are sleek, fast, and thrive in open water. This tuna is instantly recognizable by its detailed, maze-like markings along the back. These dark, irregular patterns almost look hand-drawn, giving Frigate Tuna a distinct flair compared to smoother-toned relatives.

This species prefers the upper layers of the ocean, usually staying within the top 50 meters. Schools often mix with other small tuna and pelagic fish, forming dynamic groups that swirl near the surface in search of small prey. Watching Frigate Tuna feed is a bit like watching a group of sprinters chasing scattered marbles—quick, sharp, and full of energy. Their primary diet includes crustaceans, squid, and small fish. Seasonal shifts in plankton abundance influence their movement, making them a helpful indicator of regional ecological health.

Frigate Tuna have slender bodies, metallic-blue backs, and lighter undersides. They usually weigh between 3 and 8 pounds but punch far above their weight in speed. When hooked, they streak away in long, powerful runs that give anglers an exciting challenge on light tackle. Coastal fishers throughout parts of Africa, the Pacific Islands, and Southeast Asia rely on them as a consistent food source.

In the kitchen, Frigate Tuna is used in various ways: smoked, grilled, sautéed, or preserved. Its flesh is slightly darker than that of Skipjack but milder than that of Little Tunny. Many traditional dishes incorporate it with aromatic spices or citrus marinades. For communities that depend heavily on seasonal fish harvests, Frigate Tuna represents both nutrition and cultural heritage.

Ecologically, the species supports a large array of predators. Sharks, billfish, and larger tuna frequently target Frigate Tuna schools, especially during migrations. Their high reproductive rate helps maintain stable populations even in heavily fished regions, though monitoring remains important to prevent unexpected declines.

Whether appreciated as an energetic sportfish or valued as a reliable food resource, Frigate Tuna holds an essential place among the smaller but significant Types of Tuna found around the world.

13. Kawakawa

Kawakawa—also known as Hardtail Tuna—is a widespread species found throughout the Indo-Pacific region. It thrives in both coastal waters and offshore zones, often cruising near coral reefs, drop-offs, and areas where baitfish concentrate. Its appearance is bold and easy to distinguish: dark mottled markings decorate the upper back, while the belly remains clean and silvery. Many fishers learn to recognize Kawakawa by these scattered spots alone, which resemble splashes of ink across the skin.

This tuna reaches moderate sizes, often between 10 and 25 pounds. Despite its stocky design, Kawakawa moves with impressive agility. When hooked, it tears through the water with short, aggressive bursts, earning a reputation as a spirited opponent. Anglers targeting reef predators frequently catch Kawakawa while trolling, especially during early morning hours when baitfish schools are active.

Kawakawa’s diet consists primarily of sardines, anchovies, squid, and small crustaceans. These feeding habits often bring the species close to beaches and shallow waters, making it accessible for small-scale fishers. In many coastal communities, children grow up watching Kawakawa schools chase bait right up to the shoreline—a memory that becomes a lifelong connection to the sea.

Culinary use varies by region. Some cultures smoke the fish for preservation, while others prefer it grilled with simple seasoning. The meat is oily and flavorful, similar to Little Tunny but slightly lighter. It’s excellent in stews, curries, and dried preparations. Families living near coral-rich coastlines often consider Kawakawa a dependable “daily table fish.”

As part of ocean ecosystems, Kawakawa plays a dual role. It preys heavily on fast-moving baitfish while serving as a meal for marlin, sharks, and other large predators. Researchers occasionally tag Kawakawa to track coastal productivity and the shifting boundaries of warm-water currents.

With its athletic nature, striking patterns, and strong culinary value, Kawakawa deserves recognition among the many Types of Tuna covered in this guide.

14. Black Skipjack

Black Skipjack is a small, energetic species found mostly in the tropical eastern Pacific. It shares some qualities with Skipjack Tuna but carries deeper coloration and distinctive markings that set it apart. The back appears almost charcoal-black, while the belly shines silvery white. Several dark horizontal lines run along the lower sides—one of the easiest ways to identify this species at a glance.

Black Skipjack prefer warm waters near current edges, especially zones where nutrient-rich upwellings attract large numbers of anchovies, sardines, and small squid. They tend to move in tight schools that twist and turn in perfect unison, creating a hypnotic display for anyone watching from above. These feeding events attract seabirds and dolphins, making Black Skipjack part of some of the ocean’s most dramatic surface spectacles.

Although smaller than many tuna species, Black Skipjack pack an impressive amount of stamina. Anglers targeting them often use small metal jigs or feather lures. Once hooked, the fish darts unpredictably, changing direction with the same energy as a child chasing bubbles in the wind. Their spirited fight makes them a popular species for light-tackle fishing along Mexico, Central America, and parts of South America.

Culinarily, Black Skipjack has darker, richer meat than Skipjack Tuna. In many coastal regions, it’s smoked, salt-dried, or used in robust stews. While not a top sashimi candidate, it delivers excellent flavor when prepared with aromatic spices or grilled over charcoal. Communities living near Pacific fishing zones often rely on Black Skipjack as an everyday protein source, especially during peak seasonal runs.

From an ecological standpoint, Black Skipjack helps regulate baitfish populations and contributes to the diets of sharks, billfish, and coastal predators. Because the species responds quickly to changes in water temperature, scientists monitor it to study the movement of warm currents and the effects of seasonal climate shifts.

Its lively nature, deep coloration, and importance within Pacific fisheries make Black Skipjack an essential species to include when reviewing Types of Tuna worldwide.

15. Slender Tuna

Slender Tuna lives up to its name with a long, narrow body that differs noticeably from the bulkier profiles of many relatives. Found throughout the Indian and western Pacific Oceans, this species prefers offshore waters but occasionally ventures near coastlines during seasonal migrations. The long-bodied shape allows it to glide through the ocean with minimal resistance, making it an efficient hunter of small fish and planktonic organisms.

The species features metallic-blue coloration along the back, fading to silver on the belly. Its fins are relatively small compared to overall body length, further emphasizing the sleek, elongated build. Slender Tuna gathers in schools that move like ribbons twisting in a gentle current—smooth, coordinated, and almost artistic.

This species is smaller than Yellowfin or Bigeye Tuna, typically reaching lengths of 20–30 inches. Its feeding strategy involves short bursts of speed followed by gliding phases, conserving energy while covering long distances. Many fishers report that Slender Tuna remain surprisingly spirited when caught, offering a lively fight despite their modest size.

Culinary uses vary across regions, but the fish is commonly grilled, dried, or preserved. The meat is firm and moderately mild, making it suitable for everyday meals in many coastal communities. Because Slender Tuna frequently appears in mixed-species schools with Bullet Tuna and Frigate Tuna, it’s often caught incidentally during seasonal fisheries.

Ecologically, the species contributes to nutrient cycles by feeding on plankton-eating fish and serving as prey for sharks, dolphins, and larger tuna. Scientists sometimes study Slender Tuna population shifts to evaluate offshore productivity and the effects of shifting currents.

With its elegant silhouette and dynamic schooling behavior, Slender Tuna adds depth to the diversity found among the many Types of Tuna highlighted in this guide. It may not receive as much attention as larger or more commercially famous species, but its ecological role and graceful movements make it an important part of ocean ecosystems.

16. Dogtooth Tuna (Gymnosarda unicolor)

The Dogtooth Tuna is one of the most legendary predators of the Indo-Pacific, feared by smaller fish and deeply respected by anglers. Despite its name, this species is not a “true tuna” in the genus Thunnus, but rather a member of the mackerel family (Scombridae). Still, in behavior, strength, and ecological role, the Dogtooth Tuna fits right in with the heavyweight champions of the ocean.

Dogtooth Tuna thrive in warm tropical waters, especially around coral reefs, steep drop-offs, underwater pinnacles, and current-rich channels. Unlike pelagic tuna that roam the open ocean, Dogtooth Tuna stay close to reef structures where prey is abundant. They are particularly attracted to areas where upwellings bring nutrient-rich waters, which attract baitfish—and which in turn attract this formidable predator.

One of the most iconic features of the Dogtooth Tuna is its mouth full of sharp, conical teeth—much larger and more pronounced than those of typical tuna. These teeth allow it to tear through tough-scaled fish, squid, and crustaceans. Combined with a torpedo-shaped body, massive musculature, and incredible bursts of speed, the Dogtooth Tuna is perfectly engineered for ambush hunting. It often strikes with explosive force, giving prey little chance to escape.

Dogtooth Tuna can reach exceptional sizes, commonly 30–70 kg, with record fish surpassing 100 kg. Their power is legendary among sport fishermen. When hooked, they dive straight downward with relentless strength. Many anglers compare the fight to hooking a freight train. This downward run is so intense that Dogtooth Tuna are notorious for breaking lines on corals or simply overpowering even heavy-duty tackle.

Ecologically, the Dogtooth Tuna plays a vital role in reef ecosystems. As a top predator, it helps regulate populations of mid-sized fish such as fusiliers, goatfish, scads, and squid. Healthy Dogtooth Tuna populations often indicate a thriving, balanced reef environment.

In appearance, Dogtooth Tuna are sleek and metallic, typically blue-green on top and silvery on the sides. They lack the finlets commonly associated with true tunas, but they make up for it with a powerful caudal fin and thick shoulders. Their coloration helps them blend into both the surface and the reef shadows, making them effective stealth hunters.

Reproduction is poorly documented due to the species’ offshore and deep-water habits, but they are believed to spawn seasonally in warm waters. Dogtooth Tuna grow relatively quickly, a trait common among active predators requiring constant feeding.

For humans, the Dogtooth Tuna is targeted both recreationally and commercially. However, it is also susceptible to ciguatera toxicity due to its reef-based diet. In many regions, large individuals are avoided as food to reduce health risks.

Overall, the Dogtooth Tuna stands as one of the Indo-Pacific’s most iconic marine predators—immensely strong, visually striking, ecologically vital, and deeply woven into the culture of sport fishing worldwide.

17. Wahoo (Acanthocybium solandri)

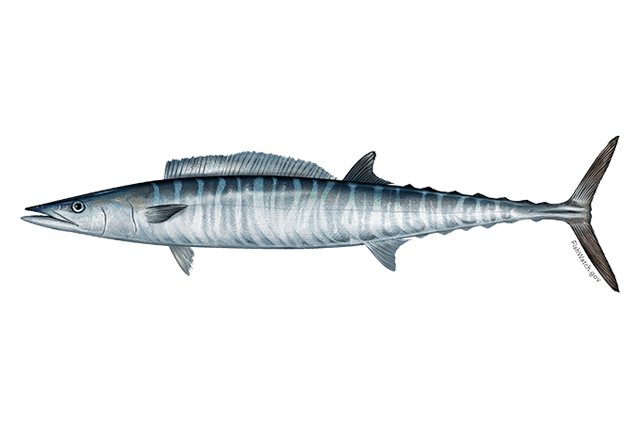

The Wahoo is one of the ocean’s most remarkable pelagic predators, known for blistering speed, razor-sharp teeth, and a streamlined body built for high-performance hunting. Found in tropical and subtropical waters worldwide, this species is often associated with offshore reefs, current lines, and temperature breaks where baitfish gather. Its speed and ferocity have made it a legend among sport fishermen and a prized catch across the world.

Wahoo are among the fastest fish in the ocean, capable of reaching speeds exceeding 75–80 km/h. Their long, torpedo-shaped bodies feature a narrow caudal peduncle, powerful tail fin, and sharp, hydrodynamic profile designed for minimal drag. They also possess keels along the tail base that act like stabilizers, further enhancing speed and maneuverability.

The most striking feature of the Wahoo is its stunning coloration. Brilliant electric-blue streaks run vertically along its metallic sides, while its back glows iridescent purple-blue. These patterns fade quickly after death, making the living fish one of the most visually spectacular predators in the sea.

Wahoo feed primarily on fast-moving prey such as flying fish, mackerel, squid, and juvenile tuna. Their jaws contain sharp triangular teeth that function like blades, allowing them to slice through prey with surgical precision. They often attack with sudden bursts of speed, tearing prey apart before returning to consume the pieces.

This species typically ranges between 10–25 kg, but exceptionally large individuals can exceed 40 kg. They often swim alone or in small groups, though during seasonal migrations they may form loose feeding aggregations. Wahoo prefer deep blue water near structures such as seamounts, drop-offs, and offshore banks, but they are fully pelagic and capable of roaming vast distances.

Reproduction occurs offshore, where females release millions of eggs into the open water. The larvae grow rapidly, feeding on small crustaceans and plankton before transitioning to a more predatory diet.

For humans, Wahoo represent the perfect combination of sport and culinary value. Their flesh is white, firm, and mild—highly prized in many cuisines and commonly served grilled, seared, or smoked. Their speed and strength make them a thrilling target for trolling fishermen, who often use high-speed lures or skirted baits to provoke strikes.

Ecologically, Wahoo are mid-level apex predators, helping control populations of smaller pelagic fish. Their migratory patterns are influenced by water temperature, currents, and food availability, making them indicators of ocean health and environmental changes.

The Wahoo stands out not only as a top predator but also as a symbol of beauty, power, and speed in the marine world. Few species combine athleticism, visual splendor, and ecological importance as elegantly as the Wahoo.

18. Mackerel Tuna (Euthynnus affinis)

Mackerel Tuna, also known as Kawakawa in some regions, is a robust and energetic species widely distributed across the Indo-Pacific. It is a close relative of true tuna but belongs to a unique lineage within the Scombridae family. Unlike large tunas that roam the open ocean, Mackerel Tuna tend to inhabit coastal waters, especially areas rich in baitfish, making them a common sight for nearshore fishermen.

This species is instantly identifiable by the distinctive dark markings on its back—irregular spots and streaks that contrast with the metallic silver on its sides. The belly is typically pale, sometimes showing faint horizontal lines. Mackerel Tuna lack the elongation of species like Yellowfin or Albacore, instead having a chunky, muscular body built for rapid acceleration.

Mackerel Tuna primarily prey on small schooling fish such as anchovies, sardines, scads, and young mackerel. They also consume squid and crustaceans. They feed aggressively near the surface, often driving baitfish into frenzied schools known as “baitballs.” Seabirds, dolphins, and other predators often join these feeding events, creating chaotic scenes familiar to offshore fishermen.

One of the notable traits of Mackerel Tuna is their preference for warm, nearshore waters. They frequently patrol coastal reefs, bays, outer islands, and areas with strong tidal flow. Their distribution is influenced by water temperature and bait availability, with peak activity occurring during periods of upwelling or seasonal migrations of prey species.

In terms of size, Mackerel Tuna are relatively small compared to larger tunas, typically weighing 3–10 kg. However, their power is impressive for their size. When hooked, they deliver fast and sustained runs, making them popular among recreational anglers.

Reproduction occurs offshore, where females release large quantities of buoyant eggs. Larvae develop rapidly and begin hunting plankton before transitioning to juvenile schooling behavior.

The species also plays an important ecological role by controlling populations of forage fish. Their presence can indicate healthy coastal ecosystems with abundant baitfish.

Although Mackerel Tuna are edible, their flesh is darker and oilier than more commercially valued tunas. They are often used as bait for larger gamefish or consumed locally, especially when fresh. Because they spoil quickly, proper handling is essential for maintaining quality.

Despite being overshadowed by larger tuna species, Mackerel Tuna stand as one of the most ecologically and recreationally important species in tropical marine environments. They are fast, aggressive, visually distinct, and tightly woven into coastal fishing traditions across many countries.

19. Spanish Mackerel (Scomberomorus spp.)

Spanish Mackerel are a group of sleek, fast, and highly migratory predators found worldwide in warm and subtropical seas. Their streamlined bodies, sharp teeth, and shimmering coloration make them one of the most recognizable coastal predators. Species vary by region, but they share similar characteristics: speed, precision hunting, and a lifestyle centered around chasing schools of baitfish.

The body of a Spanish Mackerel is long and slender, with metallic silver sides decorated by distinctive yellow or orange oval spots. These spots are key identification features and reflect sunlight beautifully when the fish is near the surface. Their dorsal surface is typically blue or green, providing excellent camouflage from above.

Spanish Mackerel are built for speed. Their tapered body, narrow tail base, and powerful forked tail allow rapid acceleration when chasing prey. They possess sharp, narrow teeth designed to slice through schooling fish such as sardines, anchovies, pilchards, and juvenile mullet. When hunting, they often strike with such force that prey schools scatter instantly.

This group of fish performs long migrations driven by seasonal temperature changes and prey availability. They often travel along coastlines, allowing fishermen to anticipate their movements during peak seasons. Their preference for warm water makes them especially abundant during summer months, and they often congregate around reefs, channels, and nearshore drop-offs.

Spanish Mackerel range widely in size depending on species. Smaller ones weigh 1–3 kg, while larger species like the Narrow-Barred Spanish Mackerel can exceed 20 kg. Regardless of size, all Spanish Mackerel are known for their fierce fighting ability and strong, sprinting runs when hooked.

Reproduction occurs in open water, where females release thousands of buoyant eggs that drift with currents. Their rapid growth helps maintain population resilience despite heavy fishing pressure.

From an ecological perspective, Spanish Mackerel are important mid-level predators. They regulate small pelagic fish populations and serve as prey for sharks, billfish, and dolphins. Their movements often reflect changes in coastal ecosystems, making them useful indicators for environmental monitoring.

Culinarily, Spanish Mackerel are highly valued. Their flesh is rich, oily, and flavorful—perfect for grilling, smoking, frying, and sashimi in some regions. The meat spoils quickly, so freshness is critical.

Spanish Mackerel represent one of the most dynamic and iconic coastal predators—fast, elegant, and ecologically vital across tropical and subtropical oceans.

20. Striped Bonito (Sarda orientalis / Sarda spp.)

Striped Bonito are energetic, fast-swimming members of the Scombridae family, closely related to tuna and mackerel. They inhabit warm waters of the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans, often traveling in schools near the surface where baitfish are abundant. Their explosive speed, striking appearance, and aggressive feeding behavior make them a favorite among anglers and an important predator in marine ecosystems.

Striped Bonito are instantly recognizable by the dark, diagonal stripes running along their upper body. These stripes separate them from other bonito species and give them a distinctive, muscular look. The body is torpedo-shaped, with metallic silver sides and a powerful tail designed for high-speed pursuits.

This species is known for its preference for nearshore and offshore waters with strong currents and plentiful bait. They frequently hunt anchovies, sardines, squid, and small mackerel. Their jaws contain sharp teeth, enabling them to slice through prey swiftly. When feeding, Striped Bonito create chaotic surface disturbances as they charge into baitfish schools, pushing them into tight balls.

They typically weigh 2–6 kg, although larger individuals can reach 8–10 kg. Despite modest size, their strength and speed make them formidable opponents when hooked. They are known for long surface runs, rapid direction changes, and relentless energy—a thrill for light-tackle enthusiasts.

Striped Bonito are highly migratory, moving seasonally based on water temperature and food availability. They travel in fast-moving schools that can stretch across large areas of ocean. Their schooling behavior offers protection from predators and increases feeding efficiency.

Reproduction occurs offshore. Females release numerous eggs that float freely until hatching. Young bonito grow quickly and join juvenile schools, forming dense groups that are often preyed on by larger pelagic species like tuna, wahoo, and billfish.

Ecologically, Striped Bonito are crucial links in the marine food web. They help manage populations of small pelagic fish and serve as prey for apex predators. Their abundance and frequent presence near the surface also make them essential indicators of ocean productivity.

From a culinary standpoint, Striped Bonito are edible but less sought after than true tuna. Their flesh is darker and stronger in flavor. They are commonly used fresh, smoked, or as bait for targeting larger gamefish. In some cultures, smaller bonito species play a major role in traditional dishes.

Overall, Striped Bonito are dynamic, fast, and ecologically important predators that enrich tropical and subtropical marine ecosystems. Their energetic behavior, distinctive markings, and essential role in food webs make them one of the ocean’s most fascinating mid-sized pelagic species.

21. Pacific Bonito

The Pacific Bonito is often the first tuna-like fish anglers encounter along the western coastline, yet it remains one of the most interesting species to watch in the open water. Although smaller than most oceanic tuna, it carries the same speed-driven lifestyle. You’ll notice that Pacific Bonito travel in loose schools that rise and fall with shifting currents, appearing almost like a flicker of silver in the surf. Their distribution stretches from Baja California up to British Columbia, where water temperatures tend to decide how far north they venture in any given season. Many coastal residents recall seeing large surface boils during warm summers, a sign that bonito are feeding aggressively on anchovies, sardines, and small squid.

Pacific Bonito have a long, sleek body with dark oblique stripes along the upper half—an easy identifier if you ever see one up close. Their torpedo shape helps them shoot across the surface in tight arcs as they try to intercept prey. While they don’t reach the massive size of bluefin or bigeye tuna, their compact frame is packed with muscle. Most weigh between 4 and 12 pounds, though occasional individuals push toward the upper teens. If you’ve ever handled one, you might compare it to gripping a tightly wound spring.

Behaviorally, the species is known for rapid bursts of speed, changing direction with surprising agility. These movements help them evade marine predators such as sea lions, sharks, and larger tuna. Some boaters joke that bonito seem to enjoy a good chase, darting across wake turbulence as if they’re playing. Though that’s a touch anthropomorphic, it’s hard not to appreciate their energy.

From a biological perspective, Pacific Bonito prefer waters that stay between 60–72°F. Seasonal shifts prompt them to move, and schools often appear suddenly near coastal headlands, piers, or kelp forests. Because they feed near the surface, their presence becomes predictable during baitfish surges. Fishermen often report that once bonito locate a cluster of anchovies, the entire area erupts with diving birds—an easy giveaway for anyone watching from shore.

In terms of anatomy, their sharp teeth and strong jaws allow them to grab slick prey items without hesitation. Their coloration also plays a role in avoiding detection. The striped pattern breaks up their outline from above, while their silver belly blends into the shimmering surface when viewed from below. It’s a simple visual trick but remarkably effective.

Interestingly, Pacific Bonito have a long association with local coastal communities. Some anglers pursue them for sport, appreciating their hard-charging fight. Others prefer them for culinary uses, though preparation techniques vary widely. Because the meat can lean towards the firm and flavorful side, many recommend grilling or smoking.

Although sometimes confused with skipjack tuna due to similar shape and coloration, Pacific Bonito can be differentiated by their distinct stripes and slightly heavier head profile. When identifying at sea, those stripes are your best clue, especially if you catch a glimpse of the top half while the fish darts under the boat.

In the broader discussion of tuna relatives, the Pacific Bonito stands as a transitional species—fast, pelagic, and powerful, yet accessible to those who spend time near the coast. They represent the rhythm of ocean life, appearing when baitfish flourish and fading away when colder water sets in. If you ever spot a sudden cluster of diving seabirds along a warm summer shoreline, you might just be witnessing a bonito frenzy.

22. Indian Ocean Longtail Tuna

The Indian Ocean Longtail Tuna is one of the most widespread tuna species across tropical waters, yet it rarely gets the spotlight compared to giants like yellowfin or albacore. Locally called “Thalapath” in parts of South Asia, this species plays a vital role in coastal fisheries from East Africa through Southeast Asia. Their distribution and seasonal movements are closely tied to warm currents, making them a familiar sight to fishermen who depend on monsoon patterns.

Longtail Tuna thrive in waters ranging from 70–86°F, though they occasionally push into cooler areas if food availability is high. Their movement patterns can appear unpredictable at first glance, but after observing them across seasons, you’ll notice they follow plankton blooms and baitfish migrations. One fisherman I once spoke to compared them to “travelers following a buffet line,” which isn’t too far off the mark.

Visually, the Indian Ocean Longtail Tuna stands out due to its noticeably elongated tail—hence the name. The finlets and streamlined body resemble other true tunas, but the lengthened upper and lower lobes of the caudal fin give them exceptional thrust. Watching one make a sharp turn feels like watching a knife slice through water.

Their coloration typically features a darker blue top fading into silver along the belly. Unlike some other tuna, they don’t show pronounced spotting or banding. Instead, their clean gradient offers excellent camouflage whether they’re hunting near the surface or deeper down. This coloration is especially useful when they pursue prey like mackerel, sardines, or small cephalopods.

One of the most fascinating aspects of the Indian Ocean Longtail Tuna is their cooperative hunting behavior. Schools sometimes drive baitfish upward, causing a surface explosion of splashes and diving seabirds. Divers often talk about hearing the low-frequency thrum of many tunas moving together, like distant drums echoing through the water.

From a biological standpoint, Longtail Tuna grow to modest sizes compared to bluefin or bigeye. Adults typically weigh between 10 and 40 pounds, although individuals exceeding 60 pounds have been recorded. Their growth rate depends heavily on food supply and water temperature.

Local coastal communities rely heavily on this species. In countries like Sri Lanka, Maldives, and India, longtail tuna support both artisanal and commercial fisheries. Fresh catches are often sold in morning markets, where the fish’s appearance—gleaming silver sides and firm flesh—signals quality.

Because they’re fast swimmers, catching them requires careful technique. Fishermen often use feather jigs, small spoons, or live bait, especially during surface feeding events. Those who target everything from reef edges to wide-open bluewater know the thrill of seeing a longtail streak out of nowhere to grab a bait.

As global waters warm, some researchers believe longtail tuna may shift their distribution slightly. For coastal regions depending on stable tuna populations, this movement poses interesting challenges. Even so, the species remains resilient, constantly adapting to shifting currents and food availability.

In the broader spectrum of Types of Tuna, the Indian Ocean Longtail Tuna demonstrates how diverse and adaptable the group can be. Not all tuna must be massive to play an important ecological role. Sometimes, the mid-sized species tell the most compelling stories—stories shaped by local culture, ocean cycles, and the fast-paced lives these fish lead every single day.

23. Atlantic Little Tuna (Euthynnus alletteratus)

The Atlantic Little Tuna, often called “False Albacore,” is one of those fish people tend to underestimate until they actually see it tearing through a bait ball with surprising speed. This species plays a big role in coastal food webs, especially across the western Atlantic. And even though it is smaller than the heavyweight tunas, it has its own place among the important pelagic hunters. Many anglers enjoy the chase, as this fish is known for fast bursts and unpredictable movement. It’s a lively species that rewards patience and a bit of persistence.

One thing that sets the Atlantic Little Tuna apart from many others is its strong preference for nearshore areas. While species like Yellowfin or Bluefin often roam offshore, this one stays close to beaches, reefs, and coastal drop-offs. You’ll see them move in schools, especially during feeding periods when smaller fish such as anchovies and sardines gather close to the surface. They often travel in groups that shift direction quickly, and watching a large school sweep across the water can feel like someone flipped a switch and brought the sea to life.

In terms of appearance, the Atlantic Little Tuna has a streamlined shape, but it carries distinct markings that make identification easier than one might expect. The fish has several wavy spots near the dorsal fin that resemble brush strokes. On the lower sides, faint stripes may appear, though they’re not as bold as those on species like Skipjack. The body has a deep blue-green upper half and a silver underside. Their coloration helps them blend with the shifting tones of coastal waters, giving them an advantage while hunting and avoiding predators.

One interesting detail about this species is how quickly it responds to temperature shifts. As waters warm, the fish tend to push farther north. In cooler seasons, they head south or deeper. These movements influence how anglers track them, since timing is often more important than location. While the Atlantic Little Tuna is smaller compared to species such as Bigeye or Yellowfin, it still packs a surprising amount of energy. A hooked fish may dart sideways, accelerate, then suddenly change direction, making the experience feel like a tug-of-war with a creature that weighs far more than it actually does.

This species prefers crustaceans, cephalopods, and smaller fish, and its feeding behavior is anything but slow. When conditions are right, they form aggressive feeding groups. These groups can cause surface “frothing,” which signals to anglers that the fish are locked into hunting mode. Their ability to communicate through movement alone allows the entire school to coordinate attacks on prey. It’s somewhat similar to the synchronized movement seen in mackerel or sardines but with the swift force of a small predator.

Reproduction occurs in warm waters, usually during late spring and summer. Females produce a significant number of eggs, reflecting the fast-paced nature of their life cycle. Although the fish is not among the most commercially valuable tuna, it’s important to ecosystems. Larger predators, including sharks, billfish, and even bigger tuna species, rely on Atlantic Little Tuna as a food source. Without this species, several marine food chains would be disrupted.

People sometimes confuse Atlantic Little Tuna with Skipjack or even Bullet Tuna. But once you pay attention to the pattern near the dorsal fin, distinction becomes easier. The fish’s energetic feeding behavior also helps identify it. For people who enjoy catch-and-release fishing, this species brings satisfying fights without the long exhaustion associated with large pelagic giants.

While rarely eaten in some regions, it remains a valued food fish in local markets elsewhere. It can be smoked, grilled, or made into stews. The flavor is stronger than that of albacore or yellowfin, so it appeals to people who enjoy fish with more character.

Atlantic Little Tuna doesn’t always get the spotlight, but it contributes far more to coastal ecology than many realize. It’s an adaptable species that responds quickly to environmental conditions, making it an interesting subject for marine observers and fisheries scientists. If you’ve ever walked along a pier and watched fast-moving shadows slice just under the surface, there’s a good chance this species was among them. It’s a fish that moves with purpose and force, even if it doesn’t carry the size of the more famous tuna.

24. Minor Tuna Species

When people talk about tuna, they usually focus on the major names—Bluefin, Yellowfin, Bigeye, and so on. But the oceans also contain a wide assortment of smaller or regionally limited tuna species. These “minor tuna species” may not headline commercial fisheries, yet they play meaningful roles in coastal ecosystems. They also help bridge the gap between small schooling fish and the apex predators that rely on tuna as prey. Because they’re less famous, their behaviors and characteristics often surprise new learners.

Minor tuna species are generally smaller than their more recognized relatives. Many fall within the Auxis or Euthynnus groups, though some come from lesser-known regional lineages. Their size makes them more agile, which is advantageous in nearshore waters where predators hunt aggressively and baitfish gather in tight clusters. These smaller tuna can dart into narrow feeding zones, which is something the bulkier species struggle to imitate. Their agility gives them a distinct presence in complex coastal habitats.

These species tend to form compact, fast-moving schools that operate almost like a single organism. A shift in current or a flicker of movement from prey triggers instant reaction. Watching these groups sweep across shallow waters can feel like observing a choreographed performance crafted by instinct. Although they may lack the giant size of the major tunas, they compensate with speed and efficient group behavior.

The diets of minor tuna species mostly consist of anchovies, sardines, small squid, and crustaceans. Their sharp eyesight helps them detect movement even in murky conditions. Because they often live in regions with fluctuating temperatures and unpredictable currents, they are adaptable feeders. Some can switch diets based on seasonal availability, which supports survival when prey populations vary.

One interesting aspect of these lesser-known tuna species is their influence on predator distribution. Sharks, larger tuna, and several billfish rely on them as dependable food sources. When minor tuna species gather in large schools, they attract an entire community of predators. This creates hotspots of activity that shape the behavior of numerous marine animals. In this sense, they act like pillars of coastal ecosystems, holding together the energetic interactions between prey and predators.

Minor tuna species often have subtle but attractive coloration. Their backs range from deep metallic blues to greenish tones, while their bellies are usually silver or pale gray. Some species display thin patterns along their sides, though these markings tend to be faint compared to those of Skipjack. Their body shapes vary slightly, but most maintain the classic torpedo form associated with speed-dependent hunters.

Reproduction varies by species but tends to occur in warm waters. Many produce large quantities of eggs, which increases chances of survival. Juvenile fish grow quickly, developing the agility needed to keep up with the rest of the school. Their rapid growth also makes them appealing prey, further reinforcing their ecological importance.

Because these fish don’t receive the same commercial attention as major tuna species, they often escape heavy fishing pressure. Still, some local fisheries harvest them for regional markets. Their meat is usually darker and stronger in flavor, which appeals to people who enjoy hearty fish dishes. In certain cultures, they are used in smoked preparations, traditional stews, or dried fish products.

Many recreational fishermen discover these species by accident. They might be targeting mackerel or small pelagic fish when suddenly a school of minor tuna species streaks across the water, biting quickly and vanishing just as fast. Their quick strikes can surprise anglers, and their bursts of speed offer a fun challenge even though the fish remain small compared to the heavy hitters of the tuna world.

Minor tuna species might not dominate headlines, but they remain important members of marine ecosystems. Their energy, speed, and abundance help sustain larger species. And even though they may not attract as much human attention as Yellowfin or Bluefin, they continue to play essential roles in the ocean’s coastal food chains.

25. Neritic Tuna (Coastal Tuna Species)

Neritic tuna refers to tuna species that prefer coastal, shelf, and nearshore environments rather than the deep, open-ocean habitats associated with the major pelagic tunas. These species live in dynamic areas influenced by tides, currents, and seasonal changes in water temperature. Their connection with coastal regions puts them in regular contact with a wide range of predators and prey. This makes them an important part of many nearshore food webs.

Neritic tuna species include several members of the Auxis, Euthynnus, and similar groups. Although generally smaller than offshore species, they move with incredible speed. Their bodies are designed for quick acceleration rather than the sustained, long-distance cruising seen in Bluefin or Yellowfin. This agile movement gives them a distinct identity in the tuna family. They thrive in areas where tight turns, rapid adjustments, and sudden bursts of power are necessary for survival.

Their appearance varies slightly between species, but they usually carry a streamlined body with a metallic sheen. Colors may range from steel-blue to dark green on top, with silver undersides. Some show faint banding or markings that help differentiate them from related species. These colors serve practical purposes, blending them with their surroundings. Predators approaching from above struggle to detect the fish against the dark water, while predators below see only the silver belly reflecting sunlight.

Diet is another aspect that sets neritic tuna apart. They chase smaller fish such as anchovies, herring, and sardines, but they also eat squid and crustaceans. Feeding often takes place in large groups. When a school finds prey, the water becomes a swirl of movement as fish strike with speed and coordination. These feeding events attract predators from all directions. Dolphins, seabirds, sharks, and even human fishermen watch for these frenzied patches on the surface.

Because neritic tuna remain close to coasts, they play a noticeable role in human activity. Local fisheries often depend on these fish, especially in tropical and subtropical regions. They provide accessible sources of food and economic support. Their meat varies in flavor depending on species, but many have firm, darker flesh that works well in grilled dishes or stews.

Reproduction usually happens in warm seasons. Large numbers of eggs are released into the water, maximizing the chance that some survive predation. Young fish grow fast, which helps them keep pace with their energetic lifestyle. Their early growth stages often occur near floating debris or coastal structures, where they find shelter until they can join the larger schools.

An interesting aspect of neritic tuna is their effect on predator distribution. Because these fish stay closer to shore, they pull predators with them. This can influence where sharks feed, where dolphins travel, and where larger offshore tuna occasionally come closer than expected. It’s surprising how a group of relatively small fish can shift the movement patterns of much larger species simply through their numbers and feeding habits.

Compared to the major tuna species, neritic tuna are less studied and less represented in scientific literature. Yet their importance is clear. They support coastal fisheries, maintain ecological balance, and act as key prey for larger predators. If these species declined, the effects would ripple throughout entire ecosystems.

The life of neritic tuna revolves around movement—quick decisions, sudden bursts, and collective coordination. Watching them hunt is like observing a fast-paced dance where every individual knows its role. They may be smaller and less famous than the giants of the open ocean, but their contributions to coastal waters remain vital.