Wild rabbits are more than just the fluffy garden visitors many people imagine. They are resilient, adaptable, and deeply connected to ecosystems across the globe. This identification guide explores 27 types of wild rabbits, each with its own appearance, habitat, and survival strategy. Whether you’re a wildlife enthusiast, photographer, or beginner naturalist, this comprehensive guide will help you learn how to identify wild rabbits by their unique features, behaviors, and geographic ranges. From the dense forests of Asia to the arid deserts of North America, these species tell the fascinating story of evolution, diversity, and adaptation.

1. The Riverine Rabbit (Bunolagus monticularis)

Found only in South Africa’s Karoo Desert, the Riverine Rabbit is one of the world’s rarest and most endangered mammals. Unlike the common cottontails, this species is instantly recognizable by its distinctive black facial stripe and silky brown-gray fur that blends perfectly with the arid riverbanks it calls home.

This rabbit’s most defining feature is its habitat specialization. It depends almost entirely on the dense riparian vegetation along seasonal rivers, which makes it highly vulnerable to habitat destruction. Farmers clearing land for agriculture have drastically reduced its range, leaving only a few fragmented populations. Today, fewer than 500 individuals are believed to survive in the wild.

The Riverine Rabbit is a solitary and nocturnal species, spending daylight hours hiding in shaded burrows. Its diet consists mainly of soft grasses, leaves, and small shrubs found along dry riverbeds. Interestingly, females give birth to only one or two young per year—a low reproductive rate that adds to the species’ precarious status.

Conservationists have called this rabbit a “flagship species” for South Africa’s Karoo ecosystem. Efforts are underway to restore its riverine habitats and work with local farmers to adopt wildlife-friendly land practices. Spotting one in the wild is incredibly rare, but for those lucky enough to see it, the Riverine Rabbit is a quiet reminder of how fragile biodiversity can be.

2. The Pygmy Rabbit (Brachylagus idahoensis)

The Pygmy Rabbit of North America is the world’s smallest rabbit species—and arguably the cutest. Adults weigh less than a pound and measure about 9–11 inches in length. But don’t let its tiny size fool you; this rabbit has adapted perfectly to survive in some of the harshest sagebrush deserts of the western United States.

Unlike most rabbits, Pygmy Rabbits dig their own burrows, often in deep, loose soils beneath sagebrush. These burrows provide protection from predators and extreme temperatures. The rabbit’s soft gray-brown fur helps it blend seamlessly with the dusty environment.

Diet-wise, the Pygmy Rabbit is a sagebrush specialist. During winter, it consumes mostly sagebrush leaves, which are rich in volatile oils that few other animals can tolerate. In spring and summer, it supplements its diet with grasses and forbs.

What makes the Pygmy Rabbit truly fascinating is its behavioral adaptation. It’s shy, secretive, and rarely seen in open spaces. When threatened, it often darts into the nearest burrow rather than relying on speed. Populations have declined due to habitat fragmentation and agricultural development, leading to conservation programs that protect its native sagebrush steppe.

This species plays a vital ecological role—its burrows provide shelter for other animals, including reptiles and small mammals. Learning to recognize this rabbit in the field means paying attention to subtle clues: small burrow entrances, sagebrush-dense areas, and faint tracks in the soft soil.

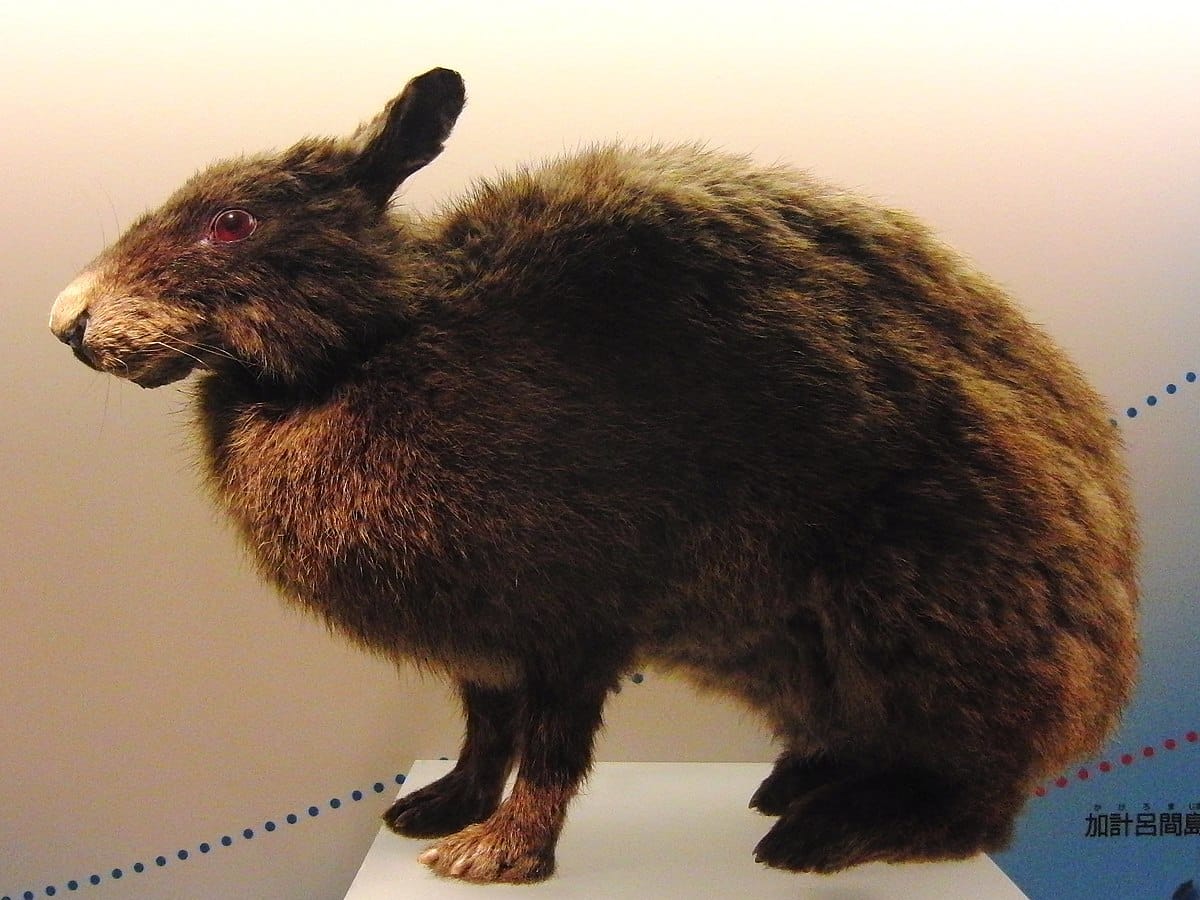

3. The Amami Rabbit (Pentalagus furnessi)

The Amami Rabbit, native only to Japan’s Amami Ōshima and Tokunoshima islands, is often called a “living fossil.” This ancient species is believed to have survived since the Pleistocene epoch, making it one of the most primitive rabbits still in existence.

Physically, the Amami Rabbit looks unlike any other. It has short ears, long claws, and dark brown fur that appears nearly black under forest shade. These adaptations help it navigate dense subtropical forests filled with ferns and undergrowth.

Behaviorally, it’s nocturnal and elusive. The Amami Rabbit spends daylight hours hiding in burrows or dense vegetation, emerging at night to feed on grasses, leaves, and shoots. Unlike many rabbits that live in colonies, this species is mostly solitary, and communication occurs through a series of low growls and thumping sounds.

Because of its limited range, this rabbit faces serious threats from deforestation and invasive predators such as mongooses and feral cats. Japan has designated the Amami Rabbit as a Special Natural Monument, affording it legal protection and conservation priority.

Ecologists see the Amami Rabbit as a key indicator species for the health of Japan’s subtropical forests. Preserving its habitat doesn’t just save one rare rabbit—it protects an entire ecosystem of plants and animals that depend on these islands’ unique environment.

4. The Eastern Cottontail (Sylvilagus floridanus)

When most people in North America think of a wild rabbit, they’re picturing the Eastern Cottontail. This species is the most widespread and adaptable of all wild rabbits, found from Canada down through Central America. Its name comes from the distinctive white fluff on its tail that resembles a cotton ball.

The Eastern Cottontail thrives in diverse environments: open fields, meadows, woodland edges, and even suburban neighborhoods. Its ability to coexist with human-altered landscapes is remarkable.

Identification is straightforward—this rabbit has a reddish-brown coat, large eyes, and long ears. During the day, it rests in shallow depressions called “forms,” hidden beneath brush or tall grass. At dusk, it becomes active, foraging on a diet of grasses, clover, and garden plants.

What sets this species apart is its incredible reproductive rate. A single female can produce several litters a year, each containing 3–8 young. This helps the population remain stable despite heavy predation by hawks, foxes, and domestic pets.

While some view them as garden pests, Eastern Cottontails are vital prey animals in North American ecosystems. They also serve as a connection point between people and wildlife—proof that even in developed areas, nature still finds a way to coexist with us.

5. The Sumatran Striped Rabbit (Nesolagus netscheri)

Hidden deep within the rainforests of western Sumatra, the Sumatran Striped Rabbit is one of the world’s least-known mammals. For decades, it was thought to be extinct until motion-triggered cameras captured images of it in the early 2000s.

This rabbit is instantly recognizable by its striking fur pattern—dark brown stripes across a reddish coat, giving it a tiger-like appearance. It’s one of the few rabbit species adapted to tropical rainforests, living among dense undergrowth at elevations between 600 and 1,600 meters.

Very little is known about its behavior, but evidence suggests it’s nocturnal and solitary, feeding on leaves, shoots, and forest vegetation. Its small population and limited range make it extremely vulnerable to habitat loss caused by deforestation and agricultural expansion.

Because it’s so rarely seen, the Sumatran Striped Rabbit has achieved almost mythical status among wildlife researchers. Ongoing camera-trap projects continue to uncover new insights into its ecology and behavior. For conservationists, each new photograph represents hope that this elusive species still thrives in the hidden corners of Sumatra’s forests.

If you ever hike through those misty mountain jungles, know that you may be sharing the forest floor with one of Earth’s most mysterious rabbits—a creature both ancient and fragile, silently carrying the legacy of an untouched world.

6. The Volcano Rabbit (Romerolagus diazi)

Known locally in Mexico as zacatuche or teporingo, the Volcano Rabbit is one of the smallest and most unique types of wild rabbits in the world. It lives exclusively on the slopes of four volcanoes near Mexico City: Popocatépetl, Iztaccíhuatl, Tlaloc, and Pelado. Standing only 10–12 inches tall, it’s a compact, round-bodied rabbit with short ears and dense gray-brown fur that helps it blend perfectly with the volcanic grasslands.

Unlike most rabbits, Volcano Rabbits prefer high-altitude pine forests and bunch-grass meadows at elevations between 9,000 and 12,000 feet. They’re rarely seen in open areas because they rely heavily on the thick tussocks of zacatón grass for both food and shelter. These grasses provide protection from hawks, weasels, and other predators, as well as cover from harsh mountain weather.

Behaviorally, the Volcano Rabbit is fascinating. It’s one of the few rabbit species that communicates through high-pitched squeaks rather than the typical thumping behavior. It lives in small colonies, where individuals build a network of runways through tall grass rather than deep burrows. Their diet consists mainly of native grasses and occasional bark, providing essential fiber for digestion.

Unfortunately, this rabbit’s limited range has made it extremely vulnerable. Urban expansion, forest fires, and grazing have fragmented its habitat, leading to a significant population decline. Conservation programs are now protecting the remaining volcanic grasslands and promoting eco-tourism that benefits local communities. Spotting a Volcano Rabbit is an unforgettable experience—like glimpsing a living symbol of resilience on the edge of an urban world.

7. The Desert Cottontail (Sylvilagus audubonii)

Among the types of wild rabbits found across North America, the Desert Cottontail is one of the most recognizable. Named after famed naturalist John James Audubon, this rabbit thrives in dry deserts, scrublands, and grasslands stretching from Montana down to Mexico. Its sandy-brown coat, large ears, and white tail allow it to disappear almost magically into the desert landscape.

The Desert Cottontail has adapted beautifully to heat and aridity. Its oversized ears are not just for listening—they act as a natural cooling system, releasing excess body heat during hot days. Instead of digging deep burrows, it takes shelter in existing dens or shaded brush piles to avoid the midday sun.

Diet is simple but efficient. It feeds on desert grasses, mesquite leaves, and cactus pads, obtaining much of its moisture from its food. During droughts, this rabbit can survive long periods without drinking water—a testament to its evolutionary mastery of desert life.

Socially, the Desert Cottontail is a solitary and cautious animal. It relies on its exceptional agility and sharp senses to escape predators like coyotes, bobcats, and hawks. When threatened, it often performs a series of zigzag jumps before vanishing into cover—a strategy that confuses pursuers.

This rabbit plays a crucial ecological role, serving as prey for nearly every desert carnivore and helping disperse seeds through its droppings. Watching a Desert Cottontail at dawn, nibbling on a patch of brittlegrass, offers a window into how perfectly adapted life can be—even in the most unforgiving landscapes.

8. The Mountain Cottontail (Sylvilagus nuttallii)

High in the Rocky Mountains and the dry plateaus of the western United States lives the Mountain Cottontail, one of the hardiest types of wild rabbits on the continent. It’s built for cold, thin air and rugged terrain—shorter ears conserve heat, and a dense gray coat offers insulation against alpine winds.

This rabbit prefers sagebrush valleys, pine forests, and rocky slopes up to 9,000 feet above sea level. It spends much of its day resting under shrubs or in abandoned burrows, emerging in early morning or late evening to feed. Its diet changes with the seasons—fresh grasses in spring, leafy shrubs in summer, and bark or twigs during snowy winters.

What makes the Mountain Cottontail remarkable is its behavioral versatility. While it generally lives alone, it may share feeding grounds with others during scarce seasons. It also uses snow tunnels and natural crevices as makeshift shelters when temperatures drop below freezing.

Reproduction happens between February and July, with females producing several litters each year. Young cottontails are born blind and hairless but grow quickly, reaching independence within a month.

For hikers and wildlife watchers, spotting a Mountain Cottontail feels like catching a brief flicker of life in the alpine stillness. Its ability to thrive where few mammals dare to live shows the extraordinary adaptability of wild rabbits to some of nature’s most challenging environments.

9. The European Rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus)

The European Rabbit might be the most influential of all types of wild rabbits—both ecologically and historically. Native to the Iberian Peninsula, it has since spread across Europe, Australia, and parts of the Americas due to human introduction. This species is the ancestor of all domestic rabbit breeds, but in the wild, it remains a clever and social creature.

European Rabbits live in complex burrow systems known as warrens, which can house dozens of individuals. These warrens are intricate underground networks with multiple entrances and escape routes, demonstrating a level of social organization rare among rabbits.

Visually, they’re medium-sized with gray-brown fur, white underbellies, and the classic cotton-white tail. They prefer open grasslands, agricultural areas, and coastal dunes where food is abundant.

Their success as a species comes from a powerful combination of rapid reproduction and adaptability. A single pair can produce dozens of offspring in a year, allowing populations to grow exponentially under favorable conditions. This same trait, however, has made them invasive in places like Australia, where their numbers devastated native vegetation and disrupted ecosystems.

Despite their reputation as pests in some regions, European Rabbits have an essential ecological role in their native range—providing food for predators such as foxes, eagles, and wildcats, and maintaining soil aeration through their burrowing activities.

They’re also central to human culture, appearing in folklore, art, and science. Understanding the European Rabbit is crucial for wildlife management, reminding us that adaptability can be both a gift and a challenge to the natural world.

10. The Brush Rabbit (Sylvilagus bachmani)

The Brush Rabbit, native to the Pacific coast of North America, represents one of the most charming yet secretive types of wild rabbits. This small, soft-furred species is found from Oregon to Baja California, favoring dense brush, chaparral, and coastal thickets where it can easily hide from predators.

Unlike its more open-country relatives, the Brush Rabbit spends most of its life in tangled vegetation, rarely venturing far from cover. Its gray-brown coat and small size make it nearly invisible in its leafy home. It uses narrow runways through the brush for safe travel between feeding and resting spots.

This rabbit’s diet includes grasses, forbs, and the leaves of native shrubs. During dry summers, it adapts by feeding early in the morning or at dusk to avoid heat stress. It doesn’t dig deep burrows but instead shelters under natural cover—fallen logs, dense blackberry thickets, or low tree roots.

Behaviorally, the Brush Rabbit is gentle yet alert. When startled, it freezes, relying on camouflage rather than flight. If escape becomes necessary, it bursts into a zigzag sprint that confuses predators. Males and females have overlapping home ranges, and breeding occurs mainly in spring, producing multiple small litters.

Although the Brush Rabbit is common in many areas, its habitat faces threats from urban sprawl and wildfire. Conservationists emphasize protecting California’s chaparral ecosystems, which shelter not only these rabbits but also many rare bird and reptile species. To spot a Brush Rabbit in the wild requires patience—and a sharp eye for movement in the dappled shade.

11. The Marsh Rabbit (Sylvilagus palustris)

Among the fascinating types of wild rabbits in North America, the Marsh Rabbit is one of the few truly adapted to aquatic environments. Found in the southeastern United States—especially in Florida, Georgia, and the Carolinas—it thrives in swamps, marshes, and wet grasslands where land and water constantly intertwine.

Unlike most rabbits that avoid getting wet, Marsh Rabbits are excellent swimmers. Their smaller ears, shorter legs, and compact bodies make them streamlined for moving through dense vegetation and shallow water. Their dark brown fur often appears almost black when wet, and their tails lack the bright white underside typical of cottontails.

These rabbits are primarily nocturnal and crepuscular, feeding during dawn and dusk on aquatic plants, grasses, and tender shoots. They often rest in hidden grassy nests during the day, blending seamlessly with the surrounding reeds.

Behaviorally, Marsh Rabbits are calm but cautious. When startled, they may dive straight into the water, paddling away silently—a behavior that sets them apart from other wild rabbits. They even use flooded areas as escape routes from predators like snakes and raccoons.

Females construct nests from grass and fur, usually on slightly elevated mounds to avoid flooding. They can produce several litters per year, ensuring stable population numbers despite heavy predation.

For naturalists, watching a Marsh Rabbit swim across a still swamp at dusk feels almost surreal. It’s a living example of how flexible and resilient wild rabbits can be—finding comfort where most mammals would sink.

12. The Swamp Rabbit (Sylvilagus aquaticus)

Closely related to the Marsh Rabbit but larger and more robust, the Swamp Rabbit—often nicknamed the Cane Cutter—is another remarkable species among the types of wild rabbits that have conquered the wetlands of the American South. It inhabits bottomland forests, riverbanks, and marshy fields, particularly across Louisiana, Mississippi, and eastern Texas.

Swamp Rabbits are sturdy creatures with thick, coarse fur in a mottled blend of brown and black, perfect for camouflage in muddy environments. They’re the largest cottontails in North America, often weighing over 6 pounds.

These rabbits are strong swimmers, capable of crossing wide streams and even floating debris-filled floodwaters. Their powerful legs allow them to leap great distances through reeds or flooded meadows when pursued. Like their marsh cousins, they rest in grassy forms by day and forage at night, eating a wide range of vegetation—cane, grasses, and sedges being favorites.

Behaviorally, Swamp Rabbits are bold. They mark their territories with fecal piles and sometimes stand their ground when approached by predators. Their breeding season lasts from February through August, and they typically have two to four litters per year.

Though adaptable, Swamp Rabbits depend on healthy wetland ecosystems. Habitat drainage and pollution have reduced their numbers in some areas, but they remain a symbol of the untamed southern wilderness. Their presence is often an indicator of thriving wetlands—proof that life flourishes even in waterlogged landscapes.

13. The Appalachian Cottontail (Sylvilagus obscurus)

Hidden among the misty peaks of the Appalachian Mountains is one of the more mysterious types of wild rabbits—the Appalachian Cottontail. Once confused with the Eastern Cottontail, this species was recognized as distinct in the late 20th century. It’s found mainly in the high-elevation forests of the central and southern Appalachians.

Appalachian Cottontails are medium-sized with soft, gray-brown fur and a slight golden tint along the neck and shoulders. Their habitat preference sets them apart: they thrive in dense mountain thickets, laurel forests, and young regenerating woodlands, usually above 2,000 feet.

Because they live in cooler, higher regions, their activity patterns are well-suited to mountain climates. They feed on mountain grasses, blackberry stems, and tree bark during winter when vegetation is scarce. Their populations are naturally fragmented due to rugged terrain, which makes them more vulnerable to genetic isolation.

Behaviorally, they’re quiet and reclusive, rarely seen in open areas. Instead of digging deep burrows, they use dense vegetation or rock crevices for shelter. During the breeding season—April to August—females build grassy nests lined with fur, often concealed under mountain shrubs.

The Appalachian Cottontail’s presence signals a healthy, regenerating forest ecosystem. Unfortunately, habitat loss from logging and development continues to pressure its populations. For wildlife watchers hiking along Blue Ridge or Smoky Mountain trails, spotting one of these secretive rabbits feels like uncovering a small, living gem in the heart of ancient mountains.

14. The New England Cottontail (Sylvilagus transitionalis)

Once common throughout the northeastern United States, the New England Cottontail is now one of the rarest types of wild rabbits in the region. It’s easily mistaken for the Eastern Cottontail, but it’s a distinct native species that has suffered greatly from habitat loss and competition with its more adaptable cousin.

This rabbit is slightly smaller and darker than the Eastern Cottontail, with a fine black line along the front of its ears. It prefers dense thickets, young forests, and shrubby fields—habitats that have declined sharply due to urbanization and land clearing.

The New England Cottontail’s story is one of conservation urgency. Populations have dwindled to small pockets in New Hampshire, Maine, and parts of New York and Connecticut. Unlike its cousin, it avoids open fields and lawns, sticking to areas where thick vegetation offers protection from predators.

Behaviorally, it’s a shy, crepuscular species, active mostly during dawn and dusk. It feeds on grasses, clover, bark, and buds, playing a role in shaping early-successional forest ecosystems.

Recognizing its perilous decline, several U.S. conservation programs have been launched to restore young forest habitats and manage competing species. The New England Cottontail is a reminder that not all rabbits are resilient generalists—some depend deeply on the delicate balance of their natural environments. Protecting them means preserving the very fabric of the northeastern landscape.

15. The Tapeti or Forest Rabbit (Sylvilagus brasiliensis)

Moving south to Central and South America, we meet the Tapeti, also known as the Forest Rabbit—a lesser-known but ecologically important member of the types of wild rabbits. Native to regions from Mexico down through Brazil and Argentina, it thrives in humid forests, grasslands, and wetlands.

The Tapeti is small and stocky, with short ears and reddish-brown fur that helps it blend into the forest floor. Unlike many open-country species, it prefers shaded environments rich in undergrowth. It’s mostly nocturnal and often uses burrows or dense root tangles for shelter during the day.

This rabbit’s diet includes grasses, herbs, and forest fruits, making it a vital seed disperser in tropical ecosystems. Its home range is small, and it rarely travels far from cover. When alarmed, it freezes motionless, relying on camouflage to avoid detection.

Tapetis breed year-round in tropical climates, producing multiple small litters annually. Their survival, however, is increasingly threatened by deforestation and hunting. In agricultural areas, they’re sometimes viewed as pests, but ecologists emphasize their importance in maintaining soil and plant diversity.

What makes the Tapeti fascinating is its ability to adapt across such a vast range of habitats—from rainforest edges to savannas—without losing its shy, forest-dwelling character. It’s a quiet, hidden link in the ecological chain of South America’s lush landscapes.

16. The Bunyoro Rabbit (Poelagus marjorita)

Native to the savannas and forests of Central Africa, the Bunyoro Rabbit—also known as the Central African Rabbit—is one of the lesser-known types of wild rabbits that have adapted to life in the tropics. Found in countries like Uganda, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and South Sudan, this species thrives in moist grasslands near rivers and wooded areas.

At first glance, the Bunyoro Rabbit looks like a typical cottontail: medium-sized, with a grayish-brown coat and a lighter underbelly. But closer observation reveals several distinctive features. It has long legs, small ears, and a sleek body, making it a swift and agile runner—an essential trait for surviving in open savannas where cover can be sparse.

Behaviorally, this rabbit is nocturnal and solitary. It spends daylight hours in shallow scrapes beneath shrubs or termite mounds, venturing out at night to feed on grasses and herbs. Unlike many rabbits that build burrows, the Bunyoro relies on natural shelters, demonstrating its adaptability to environments where digging is difficult due to hard soil.

Breeding typically aligns with the rainy season, ensuring that fresh vegetation is abundant for nursing females. Females create grass-lined nests hidden among dense vegetation, where they raise one or two litters annually.

Though not currently endangered, the Bunyoro Rabbit faces growing threats from habitat destruction and hunting. Its elusive behavior and remote range mean that little is known about its population trends. To local communities, it’s a symbol of the African grasslands—nimble, quiet, and deeply connected to the rhythm of the savanna.

17. The Manicouagan Snowshoe Hare (Lepus americanus struthopus)

While technically a hare, the Manicouagan Snowshoe Hare deserves mention among the types of wild rabbits due to its close resemblance and shared ecological niche. Native to northern Canada, this subspecies of the Snowshoe Hare inhabits boreal forests and tundra edges, thriving in cold environments few animals can endure.

The most remarkable feature of this hare is its seasonal camouflage. In summer, it sports a gray-brown coat that blends with forest undergrowth. But as winter approaches, it undergoes a dramatic transformation, turning pure white to match the snow. Its oversized hind feet—hence the name “snowshoe”—allow it to move effortlessly across deep snow.

This species plays a vital role in northern ecosystems as a keystone prey animal for predators like lynx, foxes, and owls. Its population cycles every 8–11 years, influencing the entire food web.

Behaviorally, the Manicouagan Snowshoe Hare is both shy and alert. It remains motionless when threatened, relying on camouflage, but can sprint up to 45 km/h when fleeing. Its diet consists of twigs, bark, buds, and evergreen needles during winter, switching to grasses and leaves in summer.

Although widespread, this hare faces challenges from climate change. Warmer winters and inconsistent snow cover reduce the effectiveness of its white camouflage, making it more visible to predators. Wildlife researchers monitor it closely as a living indicator of environmental change across the northern wilderness.

18. The Brushland Rabbit (Sylvilagus bachmani riparius)

A rare subspecies of the Brush Rabbit, the Brushland Rabbit is one of the most endangered types of wild rabbits in the United States. Found only in the riparian woodlands of California’s Central Valley, it occupies an extremely limited range along rivers and dense thickets.

This small rabbit is easily distinguished by its soft gray-brown coat, short tail, and subtle buff-colored flanks. It thrives in moist lowland habitats where willows and blackberries provide thick cover. Unfortunately, these habitats have been heavily modified by agriculture and urban development, leaving the Brushland Rabbit struggling for survival.

Unlike most cottontails, this species avoids open spaces and depends on dense riparian vegetation for protection. It creates intricate runways through underbrush, often using them for years. When startled, it performs quick, darting movements before freezing—a strategy that confuses predators like hawks and foxes.

Its diet includes grasses, sedges, and young shoots. Breeding occurs mainly in spring, and females typically produce two or three small litters per year.

Conservationists have classified the Brushland Rabbit as a Species of Special Concern. Restoration projects along the San Joaquin River aim to rebuild its native habitat. This small, quiet animal symbolizes the fragile balance between agriculture and wildlife in California’s rapidly changing landscapes.

19. The Hispid Hare (Caprolagus hispidus)

Among all types of wild rabbits, the Hispid Hare—also called the Assam Rabbit or Bristly Rabbit—stands out as one of Asia’s most extraordinary and endangered lagomorphs. Native to the tall grasslands of northern India, Nepal, and Bhutan, this species was once believed extinct until rediscovered in the 1970s.

The Hispid Hare’s appearance is distinctive: short ears, a blunt nose, and coarse, dark brown fur that feels bristly to the touch. Its compact body and strong hind legs make it perfectly suited for moving through thick elephant grass, where it spends much of its life concealed.

This rabbit is nocturnal, feeding mainly on wild grasses, roots, and bark. It prefers undisturbed grasslands that periodically burn—fires help maintain the open structure it needs for cover and food. Sadly, the conversion of grasslands into farmland has drastically reduced its habitat, leaving small, isolated populations.

Behaviorally, the Hispid Hare is reclusive and rarely seen. When alarmed, it dashes short distances and then freezes, trusting its camouflage over speed. It breeds during the monsoon season, producing small litters of one to three young.

Conservation efforts in India’s Kaziranga and Royal Manas National Parks aim to protect its remaining grassland habitat. The Hispid Hare represents both the vulnerability and resilience of Asia’s grassland species—a living relic from a time when vast savannas stretched across the subcontinent.

20. The Alaskan Hare (Lepus othus)

At the northern edge of the world lives the Alaskan Hare, one of the most rugged and cold-adapted types of wild rabbits on Earth. Native to western Alaska’s tundra regions, this species endures some of the planet’s harshest winters with remarkable endurance.

Large and heavily built, the Alaskan Hare has dense, white winter fur and exceptionally strong hind legs. It relies on speed and camouflage to evade predators such as arctic foxes and eagles. During summer, its coat turns gray-brown, blending with the rocky tundra.

This hare is mostly solitary, feeding on mosses, grasses, and dwarf shrubs. In the long Arctic winter, it digs through snow to find food, showing incredible persistence and adaptation. Its wide feet act like snowshoes, allowing it to move effortlessly over icy terrain.

Breeding occurs in spring, when females give birth to small litters of precocial young—fully furred and mobile within minutes. The short Arctic summer forces the species to grow and reproduce quickly before the cold returns.

To witness an Alaskan Hare in the wild is to glimpse survival in its purest form. Its resilience embodies the spirit of life on the tundra—a quiet strength that endures through endless cycles of snow and silence.

21. Dice’s Cottontail (Sylvilagus dicei)

Found only in the misty highlands of Costa Rica and western Panama, the Dice’s Cottontail—also called the Central American Mountain Rabbit—is one of the most mysterious and geographically isolated types of wild rabbits in the world. This species thrives in cloud forests and grassy meadows located more than 2,000 meters above sea level.

This small rabbit is easily identified by its dense, soft fur, which ranges from grayish-brown to dark chocolate in color, and its short, rounded ears that help retain body heat in cool mountain air. Unlike most lowland rabbits, Dice’s Cottontail is adapted to a damp, shaded environment filled with moss and ferns.

Behaviorally, it is nocturnal and solitary, spending most of the day hidden under vegetation or in natural burrows. It emerges at dusk to feed on tender grasses, shoots, and wild herbs. Its quiet lifestyle and preference for remote forests make it difficult for scientists to study, resulting in limited ecological data.

Unfortunately, this species is classified as Vulnerable due to deforestation and habitat fragmentation caused by agriculture and logging. Conservationists in Costa Rica’s Talamanca Range are working to preserve remaining forest corridors that connect isolated populations.

Dice’s Cottontail symbolizes the delicate balance of tropical highland ecosystems. Though small and shy, it plays an important role in seed dispersal and serves as prey for native predators like ocelots and hawks—helping maintain the natural rhythm of mountain life.

22. Antelope Jackrabbit (Lepus alleni)

One of the largest and most visually striking types of wild rabbits, the Antelope Jackrabbit roams the deserts and grasslands of southern Arizona and northern Mexico. Known for its long legs, enormous ears, and sleek silver-gray coat, this species is perfectly designed for speed and endurance in open habitats.

Despite its name, the Antelope Jackrabbit is not related to antelopes—but its behavior resembles them. When startled, it performs high, bounding leaps and can run up to 70 km/h, often flashing its white belly to confuse predators. Its ears act as natural cooling systems, helping it survive the intense desert heat.

This species prefers areas with scattered mesquite trees and tall grasses, where it can hide during the hottest parts of the day. It is primarily crepuscular, meaning it’s active at dawn and dusk. Its diet includes cacti, grasses, and desert shrubs, allowing it to survive long periods without water.

Breeding occurs year-round in warm climates, with females producing multiple litters annually. Each litter contains well-developed leverets that can move within hours of birth—an advantage in the predator-rich desert.

Although still common, the Antelope Jackrabbit faces habitat loss from overgrazing and land conversion. It remains a fascinating example of desert adaptation—swift, silent, and perfectly in tune with the harsh beauty of the American Southwest.

23. Japanese White Rabbit (Lepus brachyurus brachyurus)

Native to the coastal regions of western Japan, the Japanese White Rabbit (also known as the Japanese Hare) is one of Asia’s most distinctive types of wild rabbits. Its thick white fur, particularly during the snowy months, gives it a striking appearance that blends perfectly with winter landscapes.

This species inhabits a variety of environments—from coastal dunes to mountain forests—and is highly adaptable. During summer, its coat turns a reddish-brown color, while in winter, it becomes nearly pure white, allowing it to camouflage effectively against snow and predators like foxes and raptors.

The Japanese White Rabbit is primarily nocturnal, feeding on grasses, bark, and crops. Unlike domestic rabbits, it lives independently rather than in colonies, preferring solitude and relying on keen senses to detect danger. Its strong hind legs make it an excellent climber, capable of navigating rocky terrain and steep slopes.

Culturally, this rabbit holds a special place in Japanese folklore. It’s often depicted as a symbol of purity, renewal, and the moon—appearing in countless traditional stories and festivals.

Although not currently endangered, local populations face pressure from expanding agriculture and road construction. Conservationists encourage maintaining forest corridors and replanting native vegetation to support this graceful, snow-colored icon of Japan’s wildlife.

24. Tres Marías Cottontail (Sylvilagus graysoni)

Among the most endangered types of wild rabbits on Earth, the Tres Marías Cottontail exists only on María Madre Island, part of the Islas Marías archipelago off Mexico’s Pacific coast. This rare species is a unique evolutionary offshoot, having developed in complete isolation for thousands of years.

Slightly larger than mainland cottontails, it features coarse brown fur, long ears, and a lighter underside. Adapted to the island’s dry forests and rocky terrain, it feeds on a mix of native shrubs, herbs, and grasses. Because of limited resources and no natural predators, it evolved slower reproductive cycles and a calm, almost fearless temperament.

Unfortunately, the Tres Marías Cottontail has suffered greatly from habitat destruction and the introduction of invasive species such as cats, dogs, and goats, which compete for food or prey on young rabbits. Conservationists estimate its population to be critically low.

Mexico’s environmental authorities have designated María Madre Island as a biosphere reserve, restricting human access to help protect this rabbit and other endemic species. The Tres Marías Cottontail is a living reminder of how fragile island ecosystems can be—unique, beautiful, but perilously vulnerable.

25. Yarkand Hare (Lepus yarkandensis)

Native to the arid Tarim Basin of Xinjiang, China, the Yarkand Hare is one of the few types of wild rabbits adapted to true desert conditions. Its pale sandy fur, large eyes, and long ears make it look almost ghostly against the dunes of Central Asia.

The Yarkand Hare prefers riparian zones—strips of green vegetation along rivers and oases where shrubs and grasses offer both food and shelter. It feeds on hardy desert plants and can survive with minimal water by extracting moisture from its diet.

This species is mainly nocturnal, venturing out after sunset to avoid the desert heat. Its keen hearing and swift reflexes make it highly alert to predators such as eagles and foxes. Females typically have two or three litters per year, timed with short desert springs when food is most abundant.

While not officially endangered, the Yarkand Hare’s habitat is shrinking due to water diversion projects and expanding agriculture in the Tarim region. Conservationists in China have begun monitoring its population as part of broader desert biodiversity initiatives.

Graceful yet resilient, the Yarkand Hare represents life’s ability to thrive even in the harshest landscapes—a quiet survivor of one of Asia’s most extreme environments.

26. Black-tailed Jackrabbit (Lepus californicus)

One of the most recognizable types of wild rabbits in North America, the Black-tailed Jackrabbit is a true icon of the western United States. Despite its name, it’s technically a hare, known for its incredible speed and long-legged agility across deserts, grasslands, and scrublands.

Its defining features include enormous ears, a distinct black stripe down its back and tail, and powerful hind limbs that allow it to leap distances of over 3 meters in a single bound. These adaptations help it escape predators such as coyotes, eagles, and bobcats.

The Black-tailed Jackrabbit is mainly nocturnal and crepuscular, feeding on a wide variety of vegetation including sagebrush, cactus pads, and desert grasses. It can survive long periods without drinking water, drawing moisture from its food—a vital adaptation in arid environments.

This species breeds prolifically, with females capable of producing up to four litters per year, each containing several leverets. This high reproduction rate allows populations to recover quickly even after droughts or predation events.

Culturally, the Black-tailed Jackrabbit has inspired countless desert folklore tales and remains an important prey species that sustains entire ecosystems. Its incredible endurance and desert survival skills make it a timeless emblem of the American Southwest.

27. Nuttall’s Cottontail (Sylvilagus nuttallii)

Named after the British naturalist Thomas Nuttall, the Nuttall’s Cottontail is one of the more widespread types of wild rabbits found across the western United States and southwestern Canada. It thrives in dry grasslands, sagebrush plains, and rocky hillsides.

This small rabbit is characterized by gray-brown fur, large dark eyes, and the signature fluffy white “cotton” tail. Its compact build helps it navigate rocky terrain while staying low to the ground to avoid predators. Though it looks similar to other cottontails, it’s slightly smaller and adapted for colder, windier habitats.

Nuttall’s Cottontail is crepuscular, active mostly at dawn and dusk. It forages for grasses, wildflowers, and shrubs, switching to bark and twigs during winter. Its sharp teeth and digestive system are perfectly tuned for fibrous diets.

It breeds from March through September, producing multiple litters per season. Females give birth in shallow nests lined with fur and dry grass, hidden beneath shrubs. Despite its wide range, this species remains sensitive to habitat fragmentation from human activity and livestock grazing.

As one of the most adaptable wild rabbits in North America, Nuttall’s Cottontail demonstrates how small mammals evolve remarkable strategies to thrive in challenging environments—from snowy mountains to arid plains.

FAQ’s

1. What is the 3 3 3 rule for rabbits?

The 3-3-3 rule for rabbits is a guideline used by many pet owners when adopting a new rabbit. It means it takes about 3 days for your rabbit to start settling in, 3 weeks to feel more comfortable, and around 3 months to fully trust and bond with you. During this time, patience and gentle handling are key. Rabbits are naturally cautious animals, so they need time to feel safe in a new home.

2. What are the 7 classifications of rabbits?

Rabbits are classified under the following seven taxonomic ranks: Kingdom Animalia, Phylum Chordata, Class Mammalia, Order Lagomorpha, Family Leporidae, Genus Oryctolagus, and Species Oryctolagus cuniculus. These categories help scientists organize animals based on shared traits. While many people group rabbits with rodents, they actually belong to a completely different order—Lagomorpha. This distinction highlights their unique biology and behavior.

3. How many types of rabbits are there?

There are more than 300 domestic rabbit breeds and over 30 wild species around the world. The domestic breeds come in a variety of sizes, coat colors, and temperaments, from small Netherland Dwarfs to giant Flemish rabbits. Wild rabbits, such as the European rabbit or cottontail, thrive in diverse habitats. Each species has adapted to its environment in unique ways to survive.

4. Are wild rabbits friendly?

Wild rabbits are generally not friendly toward humans because they rely on their natural instincts to avoid predators. Unlike domestic rabbits, wild ones are not used to human contact and will usually run away if approached. However, if you observe them quietly from a distance, they may become curious. It’s best not to try to touch or feed them, as this can cause stress.

5. What is the most common type of rabbit?

The most common domestic rabbit breed is the New Zealand White, known for its white fur and calm nature. Among wild rabbits, the Eastern Cottontail is the most widespread in North America. These rabbits are easily recognized by their fluffy white tails and brown fur. They adapt well to different habitats, including meadows, gardens, and suburban areas.

6. Can a domestic rabbit breed with a wild rabbit?

In most cases, domestic rabbits cannot successfully breed with wild rabbits. Domestic rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus) belong to a different species than wild cottontails or hares. Even if mating occurs, the offspring are not viable. Mixing the two is also unsafe because wild rabbits may carry diseases that can harm domestic ones.

7. Is it okay to touch a wild rabbit?

It’s best not to touch a wild rabbit. Handling a wild rabbit can cause severe stress and even harm them, as they are not used to human contact. In addition, wild rabbits may carry parasites or diseases that can spread to humans or pets. If you find an injured rabbit, contact a wildlife rescue center instead of trying to handle it yourself.

8. Can wild rabbits like humans?

Wild rabbits rarely form bonds with humans because they are instinctively wary of predators. However, if you regularly spend time near them without threatening behavior, they might tolerate your presence. Over time, some wild rabbits may approach for foo

11. What is the 3 hop rule for rabbits?

The 3 hop rule refers to giving rabbits enough space to move naturally. A rabbit should be able to make at least three full hops in any direction within its enclosure. This ensures they get proper exercise and stay healthy. Rabbits are active animals that love to run and stretch, so providing room to hop helps reduce stress and boredom.

12. Do rabbits sleep at night?

Rabbits are crepuscular animals, meaning they’re most active during dawn and dusk. They don’t sleep all night like humans but instead take short naps throughout the day and night. On average, a rabbit sleeps about 8 hours in total, often with its eyes half open to stay alert for predators. Their sleeping habits are adapted for survival in the wild.

13. Can a rabbit bond with a human?

Yes, rabbits can form strong bonds with humans. With patience, gentle handling, and regular interaction, they learn to trust their owners. Many rabbits enjoy being petted, sitting beside people, and even responding to their names. Building a bond requires consistency and respect for the rabbit’s boundaries. Over time, your rabbit will show affection in its own subtle ways.

14. Is it bad to have wild rabbits in your yard?

Having wild rabbits in your yard isn’t necessarily bad, but they can sometimes cause damage to gardens and plants. They might eat vegetables, flowers, or tree bark. However, they also help with seed spreading and can be fun to watch. If you want to keep them away, using fences or natural repellents can help protect your garden without harming them.

15. Do rabbits get lonely without another rabbit?

Yes, rabbits are social animals and often get lonely when kept alone. In the wild, they live in groups and rely on companionship for comfort and safety. A single rabbit can develop depression or behavioral problems if it doesn’t have interaction with others. If you have only one rabbit, spending time daily with it can help fill that social need.

16. How to tell if a wild rabbit likes you?

If a wild rabbit doesn’t run away immediately and stays near you, it may feel somewhat safe in your presence. Calm behavior, grooming itself, or eating while you’re nearby are good signs of trust. However, wild rabbits rarely form real bonds with humans. It’s best to enjoy watching them from a distance rather than trying to interact directly.

17. Do wild bunnies carry diseases?

Yes, wild bunnies can carry diseases such as tularemia, parasites, or mites. While the risk to humans is low if you don’t handle them, it’s still wise to avoid direct contact. Pets, especially dogs and cats, should also be kept away from wild rabbits. Observing them from afar helps both you and the animals stay safe and healthy.

18. Should you leave wild rabbits alone?

Yes, you should always leave wild rabbits alone. They are self-sufficient animals that don’t need human help unless they are injured or clearly orphaned. Handling them can cause stress and sometimes even lead to death from shock. If you find a baby rabbit, it’s best to observe from a distance—its mother is likely nearby.

19. What does it mean when a wild rabbit stays in your yard?

If a wild rabbit stays in your yard, it often means your space feels safe and provides food or shelter. Rabbits are cautious animals and won’t linger in areas that seem dangerous. They might also be nesting or resting in tall grass or shrubs. It’s a sign that your yard offers a calm environment for wildlife.

20. What do rabbits hate the most?

Rabbits dislike loud noises, sudden movements, and strong smells like garlic or vinegar. They also fear predators such as dogs, cats, and hawks. When frightened, they may thump their hind legs or hide for long periods. Creating a quiet, stable environment helps keep rabbits relaxed and happy, whether they’re wild or domesticated.

21. Should you leave water out for wild rabbits?

Yes, leaving out a shallow bowl of water can help wild rabbits, especially during hot or dry seasons. Make sure the container is low and easy for them to access. Place it in a quiet, shaded area away from pets and predators. Avoid adding food like carrots or lettuce—just clean, fresh water is best for their safety and hydration.

22. How do you say “hi” in bunny language?

Rabbits greet each other through gentle body language rather than sounds. To say “hi” to your rabbit, sit quietly near them and let them approach. Softly speaking or gently extending your hand for them to sniff mimics friendly behavior. When a rabbit rubs its chin or nudges you, that’s their way of saying hello and claiming you as part of their social circle.

23. Why do wild rabbits stare at you?

Wild rabbits often stare to assess whether you’re a threat. Their vision is designed to detect movement, so they’ll lock eyes while deciding if it’s safe to stay or run. If you stay still, they might eventually relax. However, a long stare doesn’t mean affection—it’s a survival instinct that helps them stay alert in the wild.

24. Can I leave my rabbit alone for 2 days?

It’s not recommended to leave a rabbit alone for 2 days. Rabbits need fresh food, water, and social interaction daily. If you must be away, arrange for someone to check on them or use an automatic feeder and water dispenser. Prolonged isolation can lead to stress, dehydration, or even health issues due to their sensitive digestive systems.

25. What is toxic to a rabbit?

Many common foods and plants are toxic to rabbits. Avoid feeding them chocolate, onions, garlic, avocado, rhubarb, or iceberg lettuce. Certain houseplants like lilies and daffodils can also be harmful. Always provide hay, fresh greens, and clean water. When in doubt, check a safe rabbit food list before offering anything new.

26. What are bunnies terrified of?

Bunnies are easily frightened by loud noises, sudden movements, strong smells, and unfamiliar environments. Predators like dogs, cats, or hawks trigger their natural fear response. When scared, rabbits may freeze, hide, or thump their back legs. Keeping their space quiet and predictable helps them feel safe and secure.

27. Do rabbits understand human language?

Rabbits don’t understand human words like we do, but they can recognize sounds, tones, and specific cues. Over time, they learn to associate certain words—like their name or “treat”—with actions or rewards. The more consistently you speak to your rabbit, the better they’ll respond to your voice and routines.

28. Why are rabbits not allowed carrots?

Despite what cartoons show, carrots should only be given to rabbits as an occasional treat. They are high in sugar and can cause digestive problems or weight gain if eaten too often. A rabbit’s main diet should consist of hay, leafy greens, and a small portion of pellets. Carrots can be enjoyed sparingly, like a dessert.

29. What should you not do to a rabbit?

Never pick up a rabbit by its ears or scruff, shout near it, or confine it in a small space. Avoid sudden movements or chasing them, as this can cause panic. Rabbits have fragile spines and can injure themselves easily when stressed. Always approach them calmly and support their body properly when holding them.

30. Why can’t rabbits eat apples?

Rabbits can eat apples, but only in small amounts and without seeds. The seeds contain cyanide, which is toxic to them. Too much apple can also upset their stomach due to its sugar content. Offer tiny slices as an occasional treat, not a regular food source. Always remove the core and seeds before feeding.

31. How to punish a rabbit?

Rabbits should never be punished physically or shouted at. Instead, use gentle behavior correction. If your rabbit misbehaves, calmly say “no,” then redirect them to a toy or appropriate activity. You can use a short time-out in a safe pen to help them understand boundaries. Positive reinforcement—rewarding good behavior—is always more effective than punishment.

32. What time of day are rabbits most active?

Rabbits are crepuscular animals, meaning they’re most active during dawn and dusk. These times are safest for them in the wild, as predators are less active. You’ll often notice your rabbit playing, eating, or exploring early in the morning or late in the evening. During the day, they prefer to rest and nap in a quiet area.

33. Where should you not touch a rabbit?

Rabbits dislike being touched on their chin, feet, belly, or tail. These areas are sensitive and can make them feel threatened. Most rabbits prefer gentle strokes on the forehead, cheeks, or back. Always let your rabbit come to you first—forcing contact can break their trust and cause fear.

34. What is the 3 3 3 rule for rabbits?

The “3-3-3 rule” helps new rabbit owners understand adjustment time: 3 days to relax, 3 weeks to learn a routine, and 3 months to fully bond and trust their human. It reminds owners to be patient, gentle, and consistent during the transition period, especially with rescued or rehomed rabbits.

35. What country has the most rabbits?

China has the largest rabbit population in the world, both domestic and wild. It’s also one of the biggest producers of rabbit meat and fur. Wild rabbit populations are also abundant in Europe, North America, and Australia, though Australia considers them an invasive species due to their environmental impact.

36. What is a bunny with ears down called?

A rabbit with ears that hang down is called a “lop” rabbit. Popular lop breeds include the Holland Lop, French Lop, and Mini Lop. Their floppy ears are caused by a genetic trait that softens the cartilage, giving them a distinct, adorable appearance compared to upright-eared rabbits.

37. How do rabbits show affection?

Rabbits show affection in many subtle ways—nudging, grooming, flopping near you, or circling your feet. A rabbit that licks your hand or face is expressing trust and love. When they relax beside you or purr softly (by grinding their teeth gently), it’s a clear sign they feel comfortable and bonded with you.

38. What is the rarest type of bunny?

The Sumatran striped rabbit is considered the rarest rabbit species in the world. Native to Indonesia, it’s rarely seen and was thought to be extinct until rediscovered in the 1990s. Its unique striped fur and nocturnal habits make it an elusive and fascinating member of the rabbit family.

39. Can a domestic rabbit breed with a wild rabbit?

Generally, domestic rabbits cannot breed successfully with wild cottontails or hares. They are different species with incompatible genetics. Domestic rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus) can only mate with other domesticated or European wild rabbits, not North American wild species.

40. How do you know if a wild rabbit likes you?

A wild rabbit that feels comfortable around you may stay nearby, groom itself in your presence, or approach without running away. However, wild rabbits are naturally cautious and rarely show affection like domestic rabbits. Earning their trust takes time, quiet observation, and respect for their space.

🐇 Conclusion: The Beauty and Diversity of Wild Rabbits

Across every continent—from the Arctic tundra to tropical jungles—the world’s types of wild rabbits reveal nature’s endless creativity. Each species, from the desert-running Jackrabbits to the secretive Riverine Rabbit, tells a story of adaptation, survival, and balance within its ecosystem.

Understanding these remarkable animals reminds us that wild rabbits are not just symbols of fertility and gentleness—they are ecological keystones, connecting predators and plants in intricate natural cycles.

As habitats shrink and climates shift, their conservation becomes more urgent than ever.

Whether you’re a wildlife enthusiast, a student, or simply curious about the hidden wonders of nature, learning about these 30 types of wild rabbits opens a window into the delicate harmony of the wild—and inspires us all to protect it for generations to come.

Read more: